Everything Must Go

Glenn Adamson, Michael Diaz-Griffith, and Laura Doyle weigh in on inheritance, connoisseurship, and the market for old, beautiful things.

By Sarah Archer

In the mid-1980s, fragments of orange plastic Garfield telephones began washing up on the shores of Brittany’s Iroise Coast in Western France, sometimes nearly whole, sometimes in small pieces. Over the course of nearly four decades, thousands of Garfields have appeared on the beach like seashells: striped, orange, smiling, and weathered from years of bobbing along the waves. The mystery of the téléphones Garfield baffled locals for decades, and continues to cause concern for the local waterways. Full of diverse marine life and home to a very old fishing community, the Iroise Marine Nature Park was named France’s first protected marine area in 2007. The French anti-litter organization Ar Vilantsou has made the Garfields a symbol of beach pollution in the area.

The mystery was finally solved in 2019 when an experienced local fisherman saw a news report about the phenomenon and remembered that years ago a lost shipping container had become lodged in a cave that’s only accessible at low tide. He teamed up with volunteers from Ar Vilantsou and together the source of the Garfields was found at last: a nearly empty shipping container that was still—three decades later—partially stocked. Suffused with cozy pop culture associations, not useful, and not rare or antique either, the Garfield phones washed ashore as though they had been given away en masse by one of France’s older relatives in a flurry of downsizing: cheerfully, unexpectedly, and decidedly someone else’s problem now. Did anyone on the Iroise Coast ask for this? No. Do they need them? Not really. Are they cute? Bien sûr.

The Brittany Garfield phenomenon is an apt metaphor for something else: the generational transfer of stuff that’s unfolding right now from Baby Boomers to their children and grandchildren. Thousands of objects are appearing in our lives partially by design, but also through forces of nature as Americans who were born and raised in our “consumer republic,” to borrow scholar Lizabeth Cohen’s phrase, move out of their homes, donate, declutter, age, and die. The phenomenon can’t even really be called “accumulation” because it’s so often involuntary: “accruing” might be a better term for it. Collecting, by contrast, is active—even passionate. In the case of a long lost shipping container full of Tyco novelty telephones, the source is not a beloved relative but the vast machinery of the consumer economy and the profusion of cheap plastic goods that will take eons to decompose.

The Baby Boomers have more stuff than any generation before them, and their possessions will need to go somewhere: to Goodwill, to the curb, to Facebook Marketplace, to a storage unit, or in rare cases, to a prestigious auction house or even to a museum. The tidal wave of objects headed for Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z is a mixture of charming consumer detritus like les téléphones Garfield, precious heirlooms we want very much to keep, and totally random crap. Every household, even an organized one, has too much stuff. And one day we—or our heirs—will have to dispatch it all.

How do we prepare for the tidal wave, manage its fallout once it hits us, and make the best of this massive cyclic transfer of material culture? There’s a clue hidden inside the word we use to describe our most precious things, passed down from one generation to the next: heirloom. The second half of the word, loom, comes from an Old English word for “utensil” or “tool.” These objects are useful things that were handed down to children—not necessarily fancy or luxurious objects, or even costly ones. In the Middle Ages this term was almost certainly understood literally as a way of describing the practical concerns of families carrying on a business or craft, teaching each new generation how to ply their trade and perhaps improving on the techniques.

But clutter is anything but a tool. Personally I find the usefulness of an heirloom to be somewhat liberating: it shifts an object’s emotional posture from one of unresolved loss following the death of a loved one to a sense of possibility in anticipation of a different future, both for you and for it. As we stand together on the shore with our binoculars, it helps to talk to an expert. I spoke to three individuals with lots of personal and professional knowledge in this world—Glenn Adamson, Laura Doyle, and Michael Diaz-Griffith—for their thoughts.

Collecting—and what counts has an heirloom—have both changed

Glenn Adamson: Seems to me like there is a general trend away from specialist collecting and towards a more eclectic approach. This is partly led by interior designers, who have come a long way since the 1970s and are often very skilled at orchestrating complex domestic spaces including noteworthy art and design alongside antiques.

For those without the interest (or the means) to work with a professional, magazines amplify this “curatorial” approach to the home—so many individuals are also getting in on it. Even the idea of being a “collector” today sounds a little behind the times, except perhaps in the case of elite buyers of contemporary art. Most people just make spaces. They may know a lot or a little about the particular varied things they own, but the scholarly monomaniac is really a figure of the past.

So the big shift underway is away from houses that are like mini-museums to a more consciously habitable form of domesticity. In this context, the big collections of previous generations are indeed being broken up and dispersed. But emotional attachment—whether it’s to a family heirloom or something newly discovered—actually seems to me even more important than it used to be. This is sort of what I was getting at in [my book] Fewer, Better Things: People increasingly understand the objects they own to be more like relics, or reminders of friends or family, rather than things to be owned because they are valuable or “important” according to some authority or other.

Laura Doyle: We like to say that we tell the story of people and objects. I am finding—particularly with my four college-age daughters—that they want items that speak to them that they can add to their story. People are comfortable mixing styles—high and low—so it is less about a period home that we might have seen in the ’80s. I remember apartments on Park Avenue whose interiors looked like they were plucked from rural New England. Now a Windsor chair or two, or a stack of Shaker boxes, might be placed in conversation with Danish Modern chairs or an ornate French mirror. In my own home, I have a primitive American portrait hanging next to a human-sized version of the game Operation.

Michael Diaz-Griffith: As Gen X, Millennials, and even Gen Z begin to inherit the vast wealth and material culture of the Baby Boomer generation—the greatest horde amassed by any generation in world history—I think we can identify several connected but somewhat countervalent trends.

The first one is temporal: This process just won’t be as linear as previous generational handovers. On the cusp of their fifties and sixties, much of Gen X feels passed over by the opportunities for wealth and power their parents enjoyed. This is the cohort that enthusiastically embraced midcentury modern as a collecting category, as well as slick consumer brands like IKEA, and I can’t help but feel that, for them, the wave of capital will feel disappointingly belated (if welcome, as they approach retirement), and the wave of objects will feel more like an emotional burden than a gift.

Imagine Jennifer Aniston pacing athletically around a room full of inherited antiques, huffing and blowing hair out of her eyes, exasperatedly calling it all “stuff.” What do you do with “stuff”? If you’re well-off, you send it to auction or mount an estate sale; if you’re not, you liquidate it on Facebook Marketplace, plan a yard sale, or otherwise Marie Kondo it—possibly by passing it on, posthaste, to the next generation in line. This is where things get interesting. As I discuss in The New Antiquarians: Young Collectors at Home, Millennials are not minimalists. The long tail of minimalism certainly informs aspects of Millennial taste, but as a generational cohort, we’ve embraced a wildly eclectic array of aesthetic styles, periods, craft traditions, often all at once.

“Death Cleaning” is a thing, and you should start now

MDG: Anyone who is reading this who doesn’t engage in some form of “death cleaning”—tidying up after yourself while you are still alive—should begin immediately. On a grand scale, that could involve mounting a sale of things your family doesn’t want to keep before your death. Where that is prohibitive due to tax law, etc., it could mean setting the stage for such a sale—an arduous process that it is a kindness to spare others.

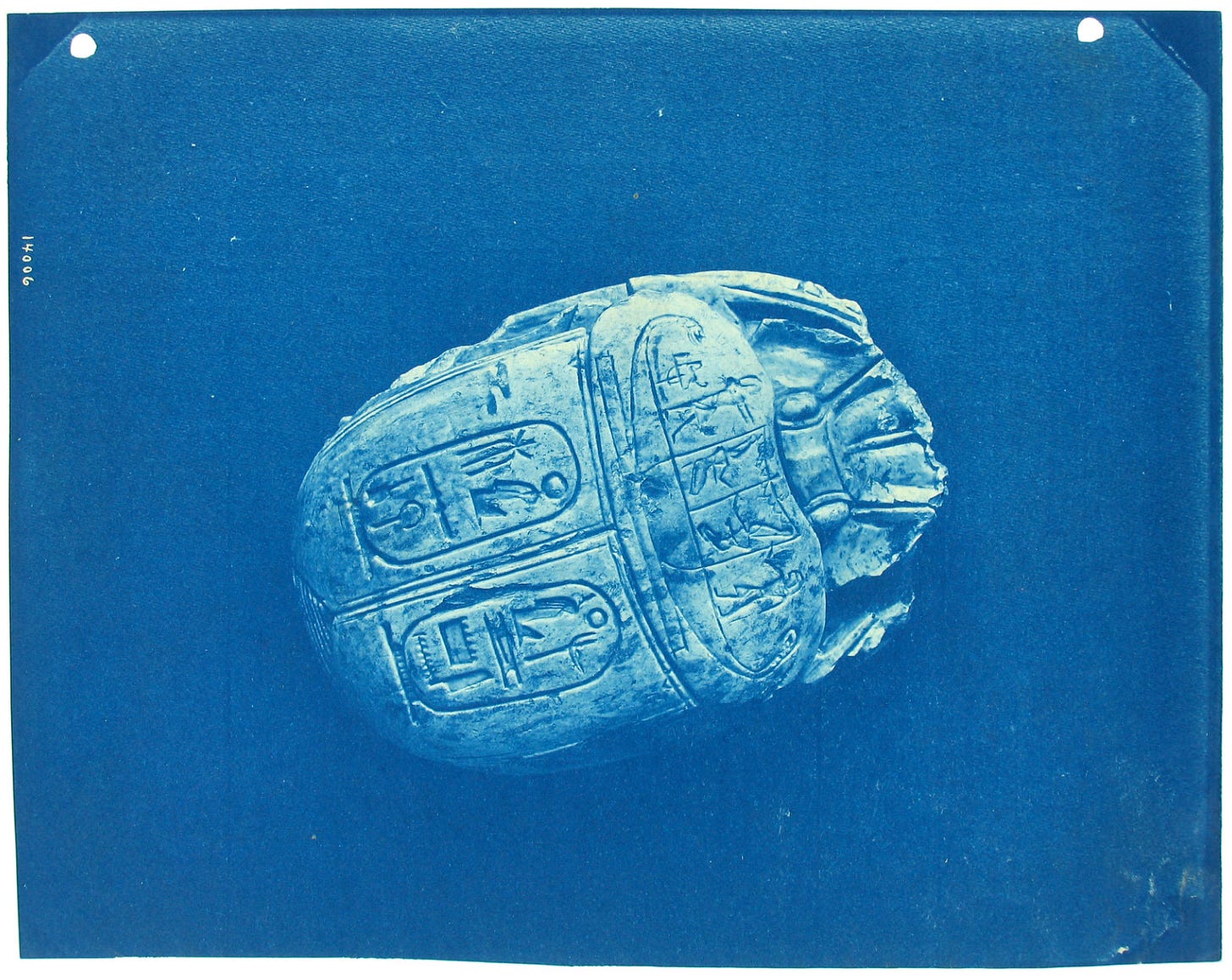

In more modest circumstances, you could do what my mother-in-law does: Every time she (an avowed Buddhist) decides to clean out a room, closet, or drawer, she asks her children what they’d like to keep from the array of heirlooms unearthed in the cleaning process. This is why I own a scarab brooch collected by my husband’s grandmother in midcentury Mexico City. What does my mother-in-law do with the rest? Who knows! Because we’ve been able to “bid” on the things we like, whether for sentimental or aesthetic reasons, or some combination of both, we are happy to be spared the details. That is a gift in itself. If the unwanted items are donated, that is my mother-in-law’s prerogative; if they are sold, they may come back around someday in the form of a financial inheritance.

Collect, keep, and edit for meaning

GA: I think about my own parents’ move from a suburban ranch house to an apartment in a retirement community. Their move out was as much a psychological as a practical challenge, because virtually everything in their home was a reminder of someone or something. What they ended up doing was taking all of my grandfather’s wood carvings with them—the new living room actually was sort of like a gallery of his work—and jettisoning most of the rest. I think for them, these family artworks had a value above and beyond their status as mementoes; they had really been invested with my grandfather’s personality. Maybe this is where craft comes into the equation. Anything can be a souvenir, but something lovingly handmade carries a lot more consequence, emotional and otherwise.

LD: My dad always said, “we just borrow these things.” We are constantly working with buyers and sellers on their collecting journeys. Many collectors are always buying and often, selling to buy more. Some put together a collection and then reach a point when they want to move on to the next one and just sell it. I think Karl Lagerfeld was famous for doing that.

When I moved 10 years ago, I wanted a fresh start. I had too much clutter. I saved the things I really loved and sold the things that didn’t bring me joy, as Marie Kondo would say. I still love that old apartment and in some ways I wish I had saved things for my children’s apartments but that would have been a lot of storage fees. But I see so much that I am constantly falling in love with new pieces. I think our tastes evolve. Take a lot of pictures, do a walkthrough video and then you can always re-experience those spaces.

MDG: Ultimately, for those inheriting collections or a large number of objects, or just trailing too many things in the wake of their lives, I think the most important question is: Do I want to live with these objects?

If the answer is no, but you can’t bear to part with a given object, you can still keep it in storage, in a trunk, in a jewelry box, in a shrine, or in some other place where it remains in your possession but is contained and sealed away from the activity of everyday life.

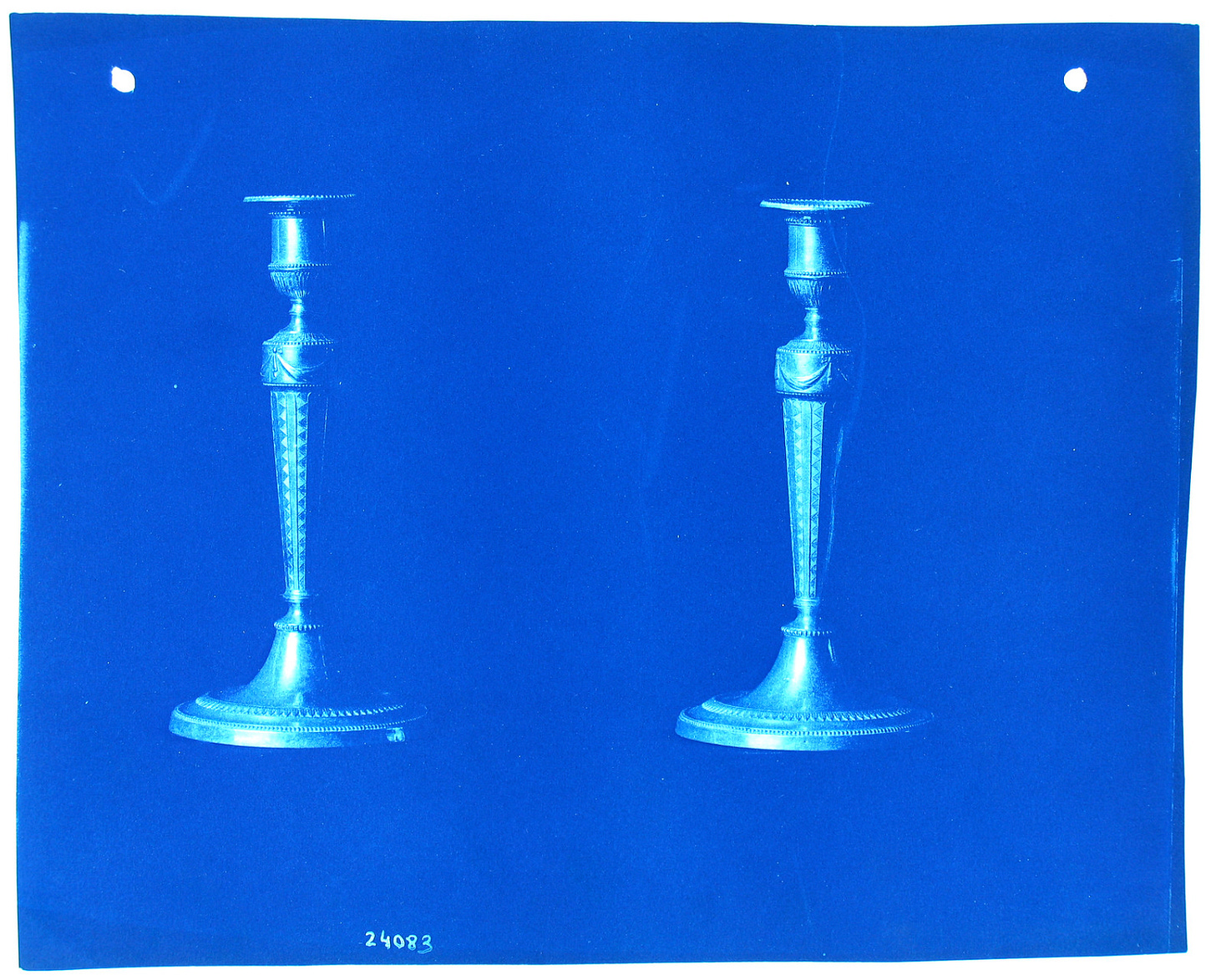

If the answer is yes, my advice is to hurl the object into circulation and really live with it. Use the inherited silver, hang the painting, eat off of the porcelain, put your feet up on the table. Hearty antiques have survived time and abuse already, and you are unlikely to destroy them; fine things, once broken, can usually be repaired and restored. But even if a treasured teacup is pulverized, so what? At least it was loved, held, used, sparked memories, and continued to enrich your life until its unfortunate demise. We only live for so long. Nothing is forever. It is best to enjoy things while we can.

Finally, while I think it’s chicer to upsize as you age, the better to host fabulous parties and masses of grandchildren, I am deeply attracted to the idea of midsizing or downsizing—perhaps even while still young. My own taste has become much more refined (in the sense of becoming more precise and subtle, not fancy!) over the past few years, and if I were to move tomorrow, I think I would sell most of my things and start over with a select few objects, pristine in their auratic importance to me, arrayed amid a great deal of negative space in a sort of John-Pawson-in-the-80s bolthole.

The good news: Now is a great time to buy antiques

MDG: There hasn’t been a better time to buy antiques and historic art since at least the 1970s, and while the antiques market—unlike the market for contemporary art—is on the upswing, it continues to strongly favor buyers. In my view, and as I’ve mentioned in my book, the battle for appreciation has been won. Contrary to the popular opinion of even a few years ago, it is now clear that younger people like, love, and even fetishize old things; and as you suggest, more and more of these things will be available on the market in the coming years.

So, we’re in a buyer’s market. All that’s needed now is for younger people to come into their buying power, whether through hard work, inheritance, or dumb luck, such that they can devote more of their disposable income to collecting, and even those of us who aren’t inheriting wealth are beginning to get there, generationally speaking—albeit in a rather apocalyptic atmosphere, thanks to our poisonous politics, the way artificial intelligence has obscured the horizon of future possibilities for younger people entering college or the workforce, etc. Because of that, my next book will focus on connoisseurship—moving from inspiration to education and, hopefully, empowerment.

Whatever your background, I want you to be able to tap into the beauty, profundity, and richness of objects, and to do so with a sense that it’s all accessible and available to you. Connoisseurship can be viewed through the glass darkly as elitist, but it’s really about developing a framework that allows you to buy things that are indeed what they are purported to be, to understand and enjoy them as fully as possible, and to do so without getting ripped off.

Overcome your fear of the auction block

GA: The auction houses, resale sites (e.g. 1st Dibs, Chairish, eBay) and antique stores have never been more full of great things at relatively affordable prices. Especially if you’re willing to cultivate an interest in currently unfashionable areas like 18th-century “brown furniture” or Arts and Crafts pottery, you could easily get something fantastic and pay a fraction of what it would have cost 20 years ago. And the “eclectic turn” I mentioned before (which, it strikes me, may have something to do with how we experience things online rather than in books, everything just one click away from everything else) is so widespread that you have an infinite number of models to look at in choosing what to buy and how to live with it.

We truly live in an age where there’s no right or wrong—which is terrible when it comes to politics, but pretty awesome on the home front.

LD: Auction is a great place to start. Ask a lot of questions—the specialists are happy to speak to new collectors and share their knowledge. Dealers are too. They often have more time to speak at fairs or in their shops. Auction is constant movement. I think it is important to remember this is a passion business. People love the objects that they are working with. Get condition reports. Set a price and include the premium, the shipping and any cost of restoration. Auction is a buying experience, and collecting is a journey. It is important to remember that the process can be part of the joy and what makes the object so special to you later. People say to buy the best you can afford, but I say: Buy what you love and you can’t go wrong.

On rediscovering design

MDG: “At some point in 2016 or so, I was the only person in the world who had referenced Dagobert Peche, the great Secessionist Wiener Werkstätte designer, on Instagram. Today I see him on social media as often as Kylie Jenner. This is not a bad thing. It’s a great thing. We are tearing through design history, discovering and popularizing what we like, and cultivating a much deeper, richer field of material culture to live with and love. In that context, I can see inherited heirlooms as more fodder for the great taste machine operating in our lives, homes, and online personae.

At the same time, Millennials tend to be very nostalgic for the pre-digital past, including the world of their grandparents, so I don’t think this tastemaking dynamic obviates the emotional resonance of heirlooms—it just means there is an imagistic glimmer around their edges.

Connoisseurship is a journey

MDG: While I love a wacky decorative scheme that plays off of antique and vintage material, etc., I really think the best (and by far the most interesting) focus for a younger collector is simply to learn about the objects, categories, and disciplines that fascinate them without worrying too much about how they will be used or displayed.

As you come to know more, you become more confident about buying; and as you earn or inherit more, you buy more; and eventually you can think about all of this business of displaying, insuring, repairing, and bequeathing objects. Along the way, however, the deeper richness of collecting is in discovering yourself, and your own taste, even if it’s at the steady clip of one object per year. Just as all things, even new ones, are on the 100-year road to becoming “antique” from the moment of their inception, any object you acquire is on the way to becoming an “heirloom.” You just have to add your hopes, dreams, memories, and meaning to it. That’s the fun part. ⌂

Editor’s note: These interviews took place asynchronously and independently, and have been edited for clarity.

Yes to all of it. Nothing is more valuable to me than my mother’s collection of knickknacks. Sorry kids, they come first.

But in all earnestness: how can a house become home if you don’t have at least some items that remind you of people you love. You might as well live in a hotel otherwise.