Go Ahead, Build Your Own Damn House

It isn't as scary as you think.

By Lila Allen

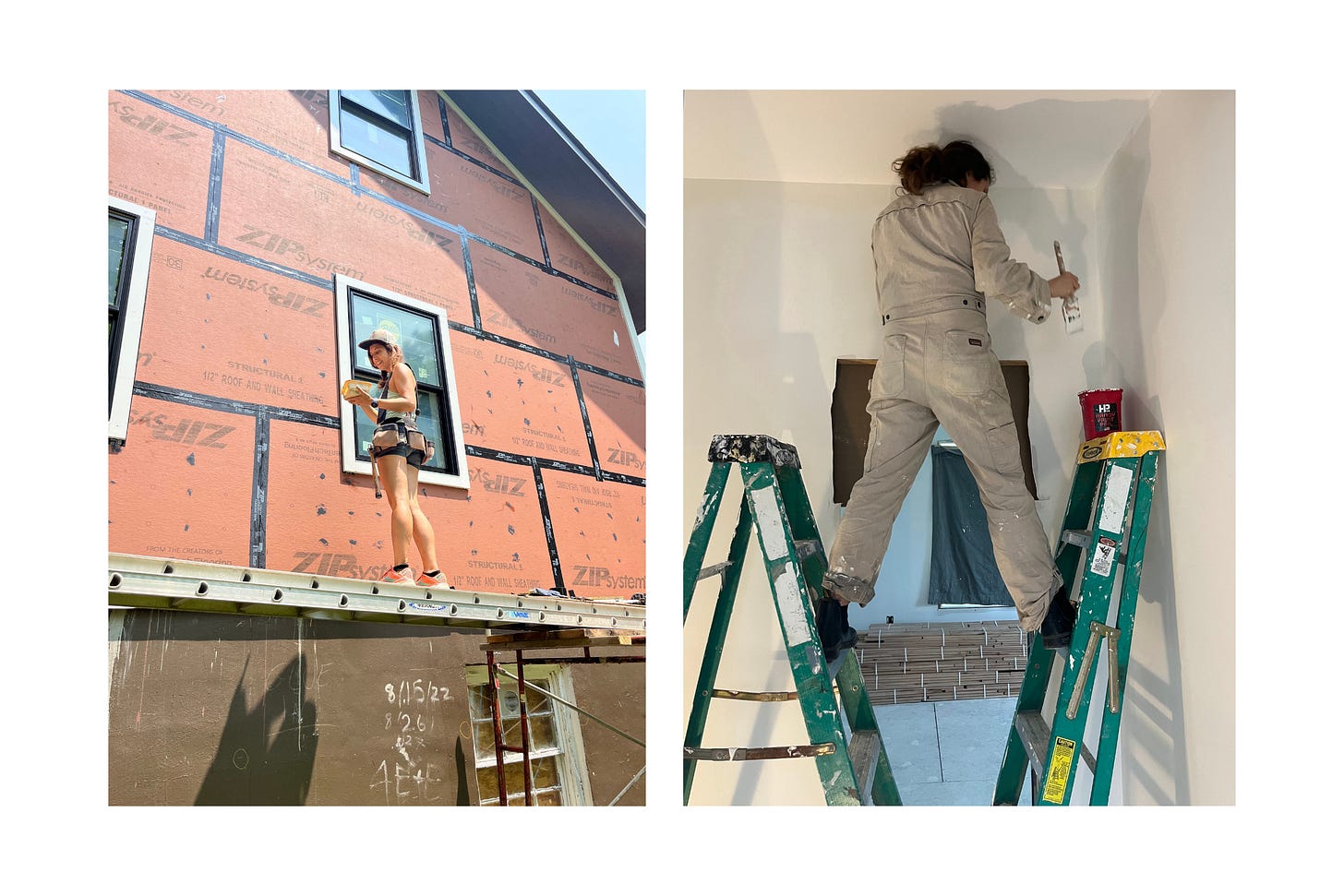

Elana Taubman and Timothy Lyons didn’t set out to build their own home from the ground up. Having purchased a fixer-upper at foreclosure in the college town of New Paltz, New York, the undertaking was initially casual, says Lyons, who back then lived in New York City: “We wanted a little house that we could put some work into, fix up, and make nice for the weekends.”

Things escalated quickly. As they became better acquainted with the property they’d purchased, its status as a teardown was undeniable. They’d have to demo the whole thing. But if they were ripping it all up anyway, they thought, why not install a basement? And if you’re going to the trouble of building the basement, why not do the first floor, too?

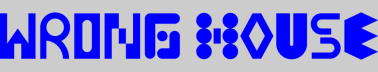

Here is the part where this couple—both of whom are teachers by profession—aren’t like most of the rest of us: They chose to do nearly the entirety of the construction themselves. The framing? Yep. The sheetrock? You betcha. They even installed the septic.

At this point I’ll reveal that the husband and wife are recounting this saga in the kitchen of the nearly-finished house, where they have lived for the past two years. There’s some missing trim here or there, but it’s not a construction site. It’s a real home. Their infant daughter, born last fall, plays on the floor behind us.

In all, the endeavor took about four years, with Lyons and Taubman completing most of the job on weekends. Lyons says that a big motivator for doing the work themselves was the cost of labor. Though they would occasionally get quotes from contractors, the prices felt hard to justify when the twosome were perfectly happy to swing the hammer or run the excavator themselves.

Three hundred miles north, the designer Jonah Takagi is embarking on a similar journey. Seeking an “unmolested”—i.e. unflipped—home in Vermont several years ago, “I couldn’t find what I was looking for,” he says. “It just seemed like the best way forward would be to build something.” Following a letter-writing campaign to landowners in the area, he purchased a near-wild 16-acre patch of earth (“somewhere between a meadow and a forest,” as he puts it). Takagi, who is self-employed, points out that inaccessibility of the traditional, mortgaged-backed path to home ownership was a factor too.

Takagi’s frustration with that route isn’t unique. In fact, it’s common: Aside from the borrowing challenges experienced by self-employed creatives with variable incomes, in 2023, nearly half of American renter households were cost-burdened. (“Cost burdened” means that more than 30% of income goes towards housing.) That kind of calculus has negative consequences on many different aspects of well-being, but it also means that saving money for a home can be difficult if not impossible. Construction loans, meanwhile, are often too restrictive for self builders.

Against this scenario, Takagi has moved methodically, paying bit by bit as his home comes closer to being a reality. Unlike the New Paltz couple, Takagi faced a dearth of existing infrastructure at his acreage in rural Vermont. He’s worked with the local electric company to run power to the edge of his property, cleared trees, and installed a driveway. Spending the bulk of his time as a furniture designer and teaching at RISD, Takagi can’t be on-site full time—and Vermont’s building season is limited due to the region’s cold weather. So far, it’s been a few years—but speed isn’t the point. “I could move in in maybe a year and a half,” he says, but it will take far longer to be really, truly done.

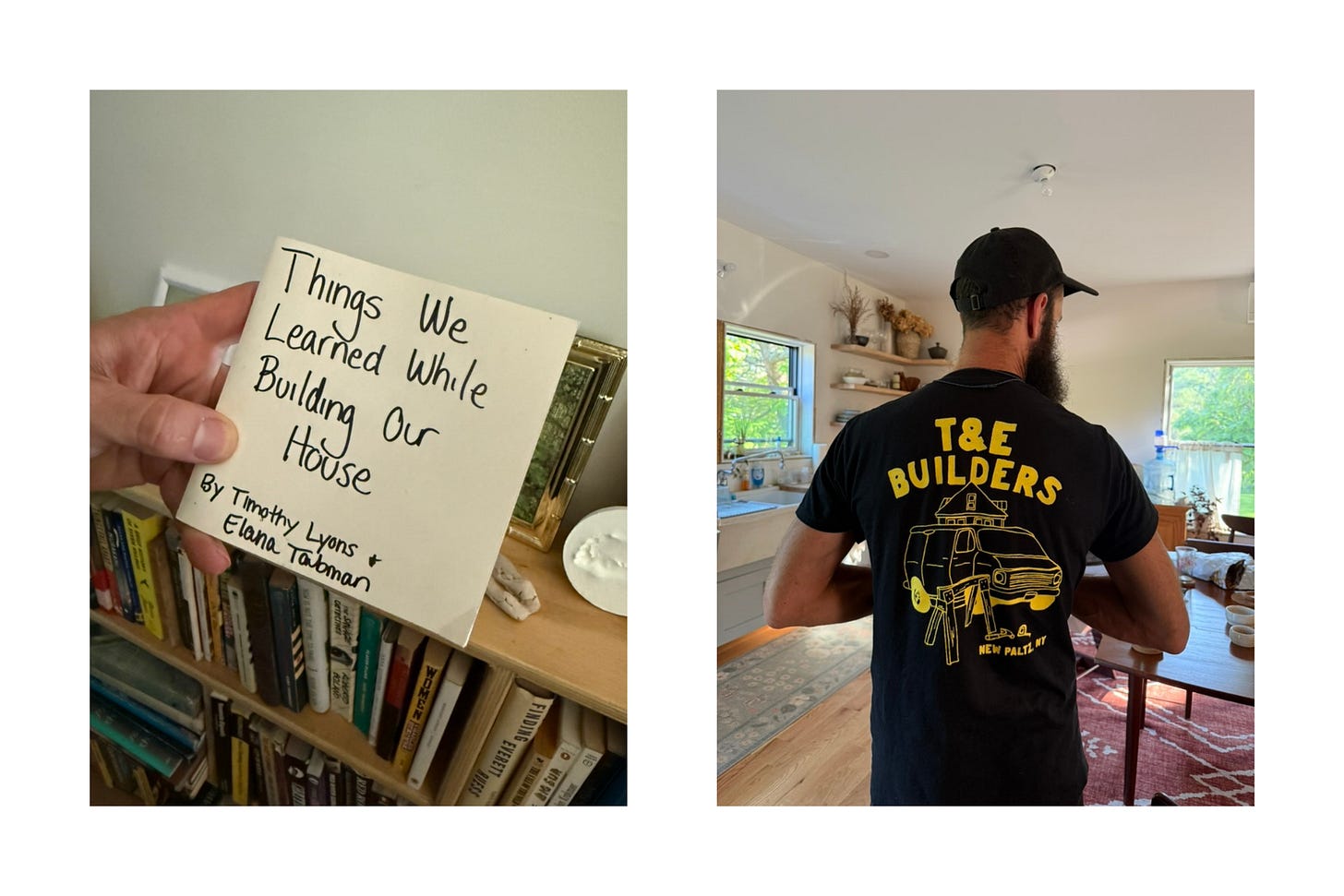

Takagi hired WOJR, a Cambridge, Massachusetts–based architecture studio, to design the house—a move that helped buoy the project, and Takagi’s spirits when things felt overwhelming. Their proposal for a square-plan, 600-square-foot structure, is designed to be built by someone like Takagi, rather than a professional construction team.

“If this were 20 years ago, I could have gotten a keg and some pizzas and had a bunch of my art school friends come up there and we could have banged this out,” says Takagi, who is in his mid-40s. “I had a frank conversation with them... like, I'm literally doing this myself.”

Tinna Harling encounters nest-seekers like Taubman, Lyons, and Takagi all the time. Egnahemsfabriken, the research and education organization she founded in Tjörn, Sweden, teaches the construction-curious how to build their own homes. When I spoke to her, her team was preparing for an upcoming workshop that would instruct attendees how to make their own green roofs.

Harling, a planning architect by training, says that the biggest challenge for self-builders isn’t a lack of skill—it’s burnout. The process of raising your own home is never going to be quick. (It took Harling herself three years to finish a guest house in her own back yard.) “It’s very important to have a process around you so you don’t feel alone,” she says. She notes that hiring an architect to do the design, as Takagi did, can prevent a lot of frustration—not to mention wasted time and material.

For many, constructing one’s own home might be a personal dream—but Harling, who witnesses builders from their 20s to their 70s cycle through Egnahemsfabriken, sees great potential in finding support systems through the construction process, too. “If you do a big project and you feel alone, then you will lose the joy of it,” she says.

Taubman and Lyons ran into their share of challenges along the way—disagreements over the positioning of the interior stairwell, and an intense build schedule that left no time for outside commitments. “We didn’t go to family events,” says Taubman. “Our whole life was building this house, thinking about it, talking about it.” But that constant negotiation and ability to face huge, complex projects, as well as a willingness to learn and make mistakes, has proved to be foundational to their family. “Everything in this house, we had a conversation about,” says Taubman. “All we do is make decisions together.” When the couple became pregnant, “We were like, OK, we can do this. We are going to disagree sometimes. But we disagreed on every single thing in this house and came to an agreement.”

The reward of your own home—of sitting in a kitchen where you hoisted the beams yourself—requires the risk that you might screw it up along the way. “Worst case scenario is you call someone in to get it done,” says Lyons. “If I'm fixing my truck and I can’t do it anymore, I’ll call a tow truck, bring it to the mechanic, and they’ll fix it. But if I can fix it myself, why would I not try?” ⌂