How “Trading Spaces” Made Us Over

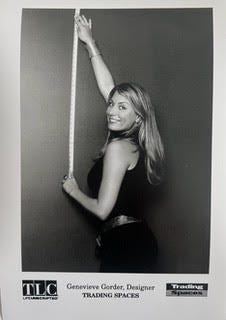

The rise of DIY TV wasn’t a fluke—it was an economic indicator. “Trading Spaces” designer Genevieve Gorder gives Wrong House a view from the inside.

By Sarah Archer

If you were domestically inclined in the early ’00s and you liked watching interior design makeovers on TV, there were few options available to you. In retrospect, this is staggering to contemplate. In 1994, HGTV took to the airwaves in 44 markets across the United States reaching about 6.5 million households. Though it got off to a relatively slow start, within a few years it was picking up steam, with 64.2 million viewers by 2000.

And back then, TLC’s “Trading Spaces”—a show where neighboring households made over a room in each others’ homes with a modest budget, designer advice, and old-fashioned elbow grease—was the crown jewel of the genre. But this show, led by host Paige Davis, carpenter Ty Pennington, and a small army of decorators, was a product of its era, driven as much by trends in an evolving American economy as it was by a shifting media diet.

The Martha Effect

Since the 1990s, Martha Stewart had commanded the various vectors of home decor synergy with an eponymous magazine, TV show, and constellation of merchandising deals and network appearances that put her style within the grasp of hundreds of millions of consumers. Stewart was hands-on, and her homes—which doubled as stage sets for her media empire—offered a mostly accessible version of the highbrow interiors that a shopper might find browsing Bunny Williams and John Rosselli’s sophisticated gardening boutique Treillage, or the aisles of Williams Sonoma. Stewart’s interior world was restrained, cultured, and idiosyncratic in its embrace of antiques, but not eccentric or threadbare. It didn’t look cheap, but it also wasn’t especially easy to replicate—and this tension was the crux of her appeal. Stewart’s partnerships with companies like Kmart and Macy’s introduced products with her aesthetic to a retail landscape that wasn’t generally known for subtlety or impeccable aesthetics. In 1998, her Martha Stewart Everyday line of home goods at Kmart was a triumph, drawing in a new swath of middle-class consumers that may not have darkened its doors previously. The products—overseen entirely by Stewart’s team—were accessible while still being designed, selected and merchandised by someone with very expensive taste.

Fast, Fun and Friendly

This media landscape reflected the reality on the ground as it had been through the early 1990s, but by the early 2000s, two important economic shifts were transforming the conditions of home renovation. The increasingly low interest rates and the lax lending requirements that would eventually contribute to the 2008 subprime mortgage crash were drawing more buyers to the housing market and encouraging the practice of house-flipping (which would also enjoy its own genre of TV shows, like “Flip This House” and “Property Ladder.”)

Although it didn’t make big headlines at the time, in May of 2000, Congress voted to normalize trade relations with China; President Clinton signed it into law in October, and China joined the World Trade Organization in December 2001. Suddenly, inexpensive imported goods were cheaper than American consumers had come to expect. (Though outlets like Ikea had previously offered relatively inexpensive goods with a sense of style, most discount stores didn’t.) Now, it was in the interest of big-box retailers to prioritize home design and tap into newly robust markets, like dorm room decorating. The advent of online shopping in the early 2000s brought the vast offerings of Wayfair and Amazon within easy reach, and specialty chains like Michaels and Hobby Lobby sold all the basic materials needed to, say, reupholster a side chair or paint an antique dresser with reasonably good results.

Right around this time, Target adopted a “Fast, Fun and Friendly” design and merchandising makeover aimed at moms and younger consumers seeking home electronics, games, sporting goods and decor. This was the moment when people started buying surprisingly chic clothes and home goods from Target’s designer collab pop-ups, and referring to the store as “Targée.” In the aftermath of September 11th, 2001, when spooked American citizens were nesting—or “cocooning” in trend forecaster Faith Popcorn’s coinage—goods were affordable, cheerfully merchandised, and oriented towards home improvement and domestic fun thanks to this confluence of economic forces.

The Rise of “Trading Spaces”

If home repair and renovation had previously been the province of experts and strongly coded as the domain of skilled middle-aged men with Big Dad Energy and stalwart opinions about insulation, the home-renovation television landscape was itself about to get an extreme makeover. Enter “Trading Spaces.” Originally conceived on the BBC as “Changing Rooms” in 1996 (the title is a pun that refers to the British term for in-store dressing rooms), “Trading Spaces” premiered on TLC in October 2000. “Trading Spaces” had a fairly straightforward premise: Two households would team up with a professional designer to complete a makeover of a room in the other’s house with the help of affable carpenter Ty Pennington and a $1,000 budget. (Accounting for inflation, that amounts to around $1,900 in today’s dollars.) Host Davis offered encouragement and chipper commentary while two of a stable of designers including Vern Yip, Hildi Santo-Tomas, Laurie Hickson Smith, Genevieve Gorder, and Doug Wilson guided the makeover process from concept to execution in two days.

To give us a sense of what it was like from the inside, interior designer and television host extraordinaire Genevieve Gorder tells Wrong House how it all came together—and the impact “Trading Spaces” had on her life and career at a particular moment in history. Over the course of her career, Gorder has been featured on over 20 design and lifestyle shows; today, you can find her on HGTV, Netflix, and The Design Network. In addition to running her own YouTube channel, Design(ish), she also collaborates with individuals and companies on design projects and collections, including a full line of furniture and decor for kids with The Land of Nod in 2017.

Sarah Archer: How did you land in the world of “Trading Spaces” initially?

Genevieve Gorder: It was a show in England before it was in the US, it was called “Changing Rooms.” It was just a huge deal over there. And of course, we didn't know how big of a deal it was. We were told it was a big deal, but we weren't really watching television as a global society then, right? So we didn't know what would happen to our lives, either, but I was introduced to it. I was working in a studio here in New York. And I was bored sitting at a desk so much. So I was struggling with the lifestyle, but was doing well at work, and I had majored in graphic design and minored in interior design and also grew up renovating and flipping houses with my family in Minneapolis. We had all that super old architecture. And in the 1980s, there was this terrible thing called white flight, and everyone in Detroit, Minneapolis—the Midwest generally—got hit hard. And there are all these vacant, beautiful houses, but people who left the city moved to these, like, paper houses in the suburbs. My mom was 20 when she had me, my dad was 24, and so they would just buy up these super cheap, beautiful old Victorians.

SA: So were you handed some tools as a kid and it was like, you were ready to go to help Mom and Dad?

GG: You know, it wasn’t so much like “handyman” as it was like stripping beautiful fluting on columns. We were relieving these houses that were suffocating from a series of bad decisions and paneling from the 1960s and ’70s—no one wanted to look Victorian or historical during those eras. So when I was a kid, we inherited a lot of those leftovers, and my parents were just stripping everything off. We were like preservationists, really learning about the architecture. You learn the vernacular—leaded glass and capitals and all of these things. And I went out West originally, and I was like, “You guys build like shit. This is a terrible apartment. I can hear there’s not enough insulation.”

SA: Was the show developed in California?

GG: Actually it was a group of producers in Tennessee creating the show. They knew it was a success in England, and they started casting, and they were only looking for “award-winning” designers. They interviewed almost 5,000 people. We were flown down in shifts looking for the six. They found me because I won some nerdy awards in my studio as a 23 year old, for [the design of] a Tanqueray gin bottle.

SA: And you weren’t nervous?

GG: I love to present design, so I’d do well in big board rooms; I loved to talk about what we did. I come from a long line of Toastmasters, so I don’t have any fear of that stuff. So then they chose the six of us. I was the baby, and off we went.

SA: When you were chosen, was it like “OK, we’ve got Vern, we’ve got Hildy, we have these different styles.” Was there an aesthetic consideration?

GG: No. And they didn’t really see what we would do with $1,000 in a room. You know, no one really knew that ’til the show started. They raised it later on, but at the beginning it was $1,000 per room. It was about democratizing design! It was about making design accessible to anyone and everyone.

And it was kids-first, because it was on after school. Eight is the magical age where you start wanting to own your space, right, make your room your own space. Wherever I was speaking in different parts of the country, there’d be a line of kids with notebooks and drawings wanting to show me what they were working on.

So there were six of us [designers], we were all different. I mean, there was an age range, for sure. And I think that demographically, kids to seniors, everybody was watching. I was the New Yorker, so they knew I wasn’t going to design like Mississippi Laurie; we were going to have a different perspective. And I brought in the younger demographic, so it worked. Like, who knew we were all so crazy and different and dysfunctionally wonderful?

“It was just us doing the work. It really was $1,000, and it really was two days—actually, less than two days, because we were sleeping, too.”

SA: What was the process like for each episode when you were going to be on—would you meet ahead of time with the family, or did they just throw you in?

GG: We were making hundreds and hundreds of shows. It wasn’t like TV now, where there are eight or 13 episodes. And it was just us doing the work. It really was $1,000, and it really was two days—actually, less than two days, because we were sleeping, too, and we were breaking down to shoot. We didn’t have any ghost designers or people: It was just us, because we wanted to make it like “Changing Rooms”—where it was real. So that [for viewers] it wouldn’t be a huge disappointment when you tried it on your own.

So [the depiction on the show] was accurate. We were fucking Tasmanian devils. And, you know, some people were great at fabric—Laurie. Some people were great at being crazy—Hildy. Some people were great at making artwork. I had more of a graphic approach with a lot of photography, a little bit of urbanity. I was the anti-Suburban Girl. We did a lot of builder grade, but I would always try to bring in good woods. So wherever I could, I crunched the budget to make and Ty [Pennington] could build. He could build beautiful things. When I was working with him, I would try and squeeze something out.

SA: This is blowing my mind, because I think it’s fair to say, 25 years since it began, that “Trading Spaces” triggered a wave of media that is still going—HGTV and “Queer Eye.” But it’s a different animal—I get the sense when I watch “Queer Eye” that the renovations aren’t “what you see is what you get.” It seems very curated, and as though for time’s sake there’s an army of elves working behind the scenes, and then there’s the dramatic reveal. So it’s interesting that “Trading Spaces” was pretty raw.

GG: We were the first transformation show. “This Old House” was filmed over the course of years in real time, and you get little peekaboos. This was the first transformation show in the US. But it wasn’t just a show; it was a movement. And you can’t plan that. It either happens or it doesn’t.

SA: It was a big part of the DIY movement.

GG: And that’s always been in existence, especially with women, you know, and they would call it “the female arts” back in the day when we just let misogyny fly. But I think what it did was give people access, in a way. This was before Google, this was before we had GPS—all of it. [People] were really living in this cocoon of thinking that they could get stuff from Home Depot and Lowe’s. Their home improvements were IKEA. And then there was Pottery Barn, Pier One, and Williams Sonoma. Pottery Barn was the standard: People really wanted to emulate every page of that catalog. It was the time of mass oatmeal shag carpeting and halogen lights. Everyone had the same shit. After there was a huge migration to the suburbs—all these pop-up paper houses. McMansions [came about] during this time, too. But there was just no attention to style in our country, unless you you were in the 1%.

SA: Right. Unless you had zillions to spend, you were kind of on your own.

GG: Yeah, and we didn’t have an old, ancient culture. We just did it. So it was like, how do we redefine what the middle class looks like? And why can’t the working class have everything that everyone else has, because creativity is free? Like, how can we fuck [this system] up? That was really what it was about, to disrupt the system. I never wanted to be an interior designer. That profession just seemed like it was for old Southern ladies—so exclusive. I’m from the Midwest, and it’s like, everything is for everybody. And at the time, some interior designers were like, “This isn’t realistic,” and it’s because, yes, interior design was scaled so specifically [to cater to the wealthy], and you can’t make money unless you’re upcharging and your clients are billionaires.

“It wasn’t just a show; it was a movement. And you can’t plan that. It either happens or it doesn’t.”

SA: Do you think that before it premiered, if you had asked a high-end designer, like, say, a Mark Hampton, “Do you want to be on TV?” that he would have been like, “Oh heavens, no!”

GG: Oh, they would have wanted to do it, but they would have wanted to do something like, PBS—fancy. But once the industry caught on, it was like, oh my god, merchandising, right? Collections! I need that microphone so that I can sell my business, then everybody and their sister wanted to try it out for it. And guess what? Hardly anyone can do it. And I’m not trying to toot my own horn, but you can’t make boring interesting, like painting a wall and talking about a rug—which is like, snore me to death. If you can’t talk about that, do projects, produce a story, and connect to people you're with at the same time, you can't do it.

SA: It strikes me that there’s a parallel between this phenomenon, which I would say partially has roots in the Martha Stewart world of like, Fine Paints of Europe and Kmart, and the high and low of designers for Target, which was kind of what Halston tried to do, but crashed into the side of a mountain attempting to do it. What excites you the most about what you’re seeing in design on platforms like Instagram or Tiktok?

GG: I actually think there are some huge vacancies. Fashion and beauty are just so voluptuous and swollen with people and things. And it is really easy to curate the quick stuff. But home is tougher, to be honest. It’s not instant. I’m building this huge YouTube channel right now as a hub for home design. We need to scale into short-form [video] in a more powerful way for renovations—not just, “Here’s how to fix this thing in a really beautiful, quick way” that’s in your face for five minutes. I haven’t seen any of those digestible bits add up to something meaningful.

SA: I suspect that part of it is that there’s been a change in how different generations feel about home—about owning a home, buying property, the idea of flipping, more people now are taking the Apartment Therapy approach: “I’m probably going to rent forever, so these are the interventions I can do.”

GG: We are at the mercy of current events and the climate, the economy, and war. And typically when shit’s really bad, like 9/11—that’s when [“Trading Spaces”] took off—people are at home. When we are fully flush, making tons of money as a nation, and the economy is great, we’re flipping, right? But we don’t flip when times are tough. We get small. And with COVID, the home design industry was booming. And as far as Americans not owning homes, this is really the first time this has become so incredibly prolific. It’s become unattainable. So for me, it’s just switching the conversation of, you know, creating modular moments, things that you can pack up and take away, but making it look like you are rooted. So how do we talk about mortgages? How do we talk about how to get “home”? Multigenerational living, yeah? It’s very exciting because it’s all changing. ⌂

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.