In Pittsburgh’s Hill District, a Village Takes Care of Itself

Offering affordable temporary housing to Black artists, The Garfield PGH invokes community and familial legacy.

Written by Lila Allen

Joseph Garfield Moss, Jr., can still remember how the aroma of his mother Rebecca’s yeast rolls wafted from the open windows of his childhood home onto Adelaide Street. Back then, there was no A/C; just a warm breeze that could carry the scent for blocks.

But it wasn’t the baked goods alone that beckoned guests—and during Moss’s youth, there were many of them. In the ’50s and ’60s, the Hill District of Pittsburgh (also known as “Little Harlem”) had been a nucleus of Black culture for decades. The local paper, The Pittsburgh Courier, was one of the most prominent Black publications in the country, and neighborhood jazz venues like the Crawford Grill drew in the genre’s greatest talents: Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Billy Eckstine. Before heading to the Grill for a night of partying, ladies would stop in at the basement of 824 Adelaide for an updo—also courtesy Rebecca, she of the yeast rolls. On the porch, her husband, Joseph Garfield Moss, Sr., hosted fests for ham radio, a pastime he picked up when he wasn’t on patrol for the local police department. (He was one of the city’s first Black motorcycle officers.)

“That house was like a magnet—a focal point of activity not only for Black intellectuals, but Black geeks,” the junior Moss recalls. His father had purchased the property when he was around four years old, and as a young boy, Moss remembers this enclave being the kind of place he could walk to school alone. “The village took care of itself,” he says.

Moss’s childhood address, 824 Adelaide, is now a destination of a different kind, though perhaps it’s actually not so different at all. Once dressed in a red brick, the home now wears a slick sheath of black paint from stoop to chimney top, its one flashy accessory being the shiny metal 8-2-4 street numbers on the front.

Joseph Jr.’s daughter, Jessica Gaynelle Moss, is the one responsible for the new duds. “I wanted to find a way to make it a landmark,” she says of the paint job. Though the property was out of the Moss family’s hands for many years, it came back to Joseph Jr. in 2006, with Jessica becoming its steward 15 years later. This spring, it reopened as something totally new, or maybe not that new at all: The Garfield PGH, a nest for Black artists in need of short-term lodging.

“It’s a Black house for Black artists,” says Jessica. An artist herself, Jessica’s practice is often social and community-driven—no doubt in part the product of her time spent working with the artist Theaster Gates. Among her projects since then has been an artist residency called The Roll Up, which she founded, and Sibyls Shrine, an art collective and residency program for Black mothers where she serves as managing director.

Several years ago, when she was arranging a stay for a guest artist, Jessica recognized a gap in Pittsburgh’s short-term housing market. “We had a series of artists coming into town, and I would put them in really nice places,” she recalls. For one resident, she lined up an attractive property in Mount Washington, a neighborhood known for its grand views and restaurant row. “I put her there, and she was like, ‘Where are the Black people?’”

So she looked elsewhere. “The next time she came, I put her in a Black neighborhood. And it was nice, but there were no amenities.” It was a Goldilocks scenario—in either direction, too much of one thing, and not enough of another. Fortunately, Jessica was already sitting on a property on Adelaide Street, and it was packed with history and symbolism as an epicenter of Black creativity.

A few grants and a six-figure renovation later, The Garfield PGH, as it is now known, is open for business. But maybe “business” isn’t the right word, as it’s hardly a moneymaking endeavor: To stay there, you must self-identify as a Black artist—something you indicate via a questionnaire that goes directly to Jessica for review. Once booked, the rate is $100 per night for a two-bedroom apartment, plus a standard cleaning fee. (Comparable properties in the area tend to run closer to $200 or more per night, plus cleaning charges.) Jessica, who is primarily based in Ft. Lauderdale, uses that money to pay a housekeeper and a “flipper,” who readies the property for the next guest.

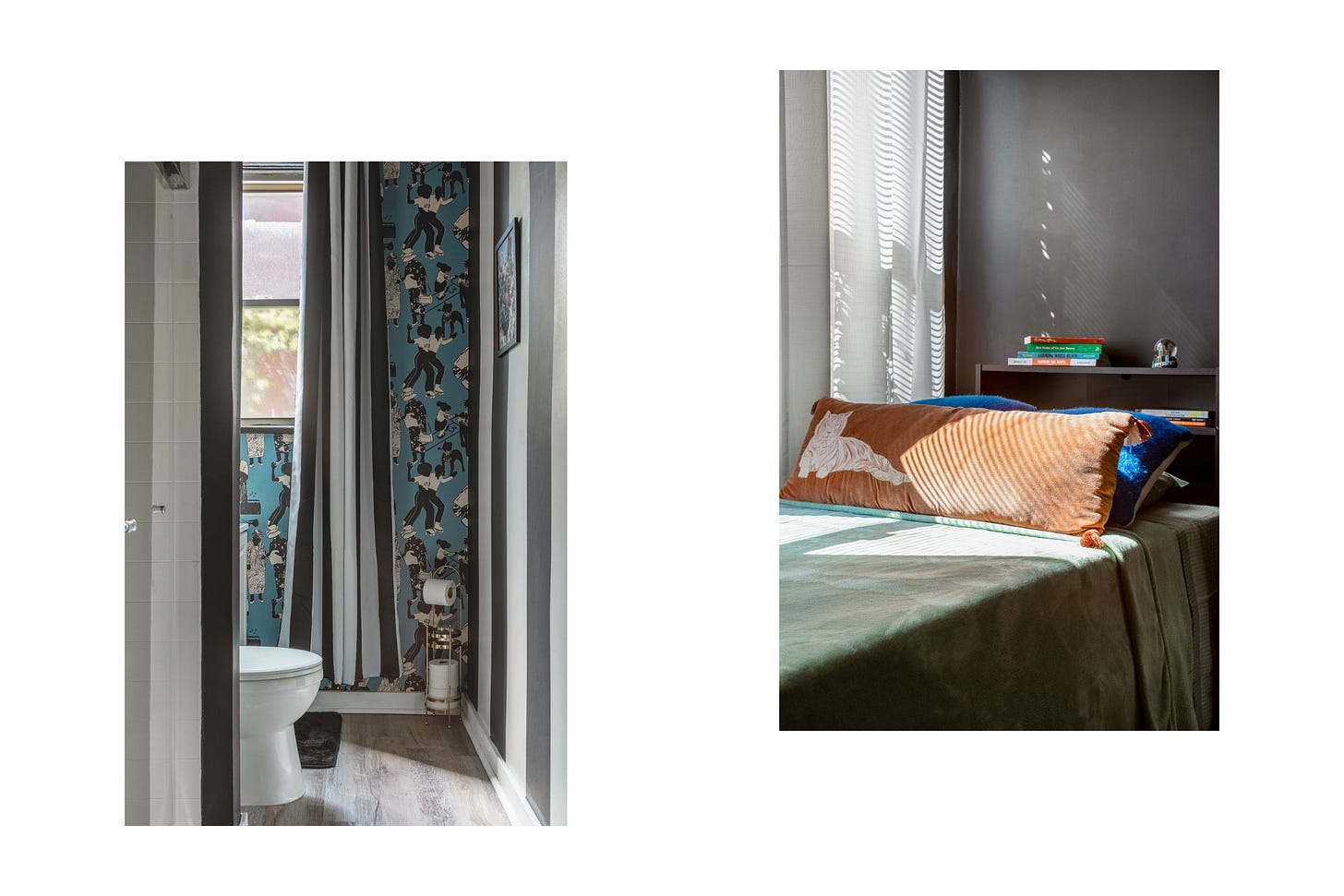

Beyond being a place for temporary housing, The Garfield PGH is an exercise in creating an all-Black economy. Inside, art from local Pittsburgh artist Darrin Milliner hangs on the walls, which are also mostly painted black. (Jessica has a zero-percent commission structure—guests can buy artwork off the wall by texting Milliner.) The Garfield’s general contractors, subcontractors, designer, muralist, cleaners, and flippers have all been Black, and at times, Jessica acknowledges, this commitment to principle has been challenging to pull off. Skilled labor is hard to find even under less restrictive circumstances, and Jessica was managing the entire affair remotely. Prices of materials multiplied during the Covid-19 bubble, pushing the Garfield farther and farther from completion. But Jessica found a lifeline through allies in the arts, and particularly in her friend and designer Nadia Hayes, who stepped in to complete the renovation, source furniture, and push The Garfield PGH over the finish line. The village took care of itself.

The history of 824 Adelaide circles around in other ways, too, at least from Jessica’s perspective. Hearing her father recount the neighborhood’s lively past as a Black cultural hub, she points out that it was the human element—the people at the center of the Hill District narrative—that drew in the community. And that’s where she sees The Garfield’s ultimate value, too. “I have reasons to get people to come,” she says. “What kind of space do I have to cultivate to help Black people feel safe enough, comfortable enough, secure enough that they can just chill? What does that space even have to look like? That’s what I’m interested in.” ⌂

I am from Pittsburgh so it's amazing to see this project come to life in the Hill District! Thank you for sharing this story.