My Prince-Themed Bedroom Was a Revolution

The “Kiss” singer taught me I could be whoever I wanted to be. Starting with my own room.

By Jesse Dorris

In 1986, I lived with my parents in a blue ranch-style home in the woods of North Dartmouth, Massachusetts. They’d moved us there after a year of renting the servants quarters of a lovely stone house in nearby Padanarum, a tony little village by the Cape Cod water. We’d moved there in a terrible break from a fairly idyllic childhood of listening to my parents’ Joni Mitchell records and riding my Hot Wheels up and down the hills of hippie, brainy Ithaca, New York. The landlord of the stone house, which dated back to the 1620s, was a friend from Ithaca. There was a big hole in the wall above my bed, which we covered with a textile. But we couldn’t afford to stay there.

The blue house was 20 minutes away, in a decidedly less desirable part of town. It, too, had holes—everywhere. The roof was constantly leaking. We discovered the skeleton of a horse in the backyard. The blue house was falling down as fast as my parents could build it back up. Faster. Neither of them were particularly handy. Neither seemed to enjoy the opportunity to create this house in their own image. I think, for them, it was a site of constant failure. My dad was a university professor, and I wonder if the house’s condition was a sign he hadn’t mobilized himself quite as far as he’d hoped from his childhood as the son of a coal miner, growing up in a dirt-floor house in a one-stoplight town called Providence, Kentucky. My mom worked at a leftist non-profit in New Bedford, and had to sue it for sex discrimination, and I wonder if this lack of a secure place to call home recalled the endless moving and misogyny of her childhood spent on army bases. My parents didn’t hide their unhappiness. Rain came into the house through plastic tarps. I spent most of my time listening to Prince and the Revolution. I was 10, and there was a lot I wasn’t able to hide, either.

That year, Prince released the album Parade. His early records had this amazing banner on them: produced, arranged, composed, and performed by Prince. As the kind of kid who spent most of his time alone, that self-sufficiency comforted and intimidated me. But then he’d found a band, and that was interesting—that you could find your people like that. Parade was a left turn towards Euro irony from the psychedelic previous album Around the World in a Day, itself a sharp twist from the pop-metal blockbuster Purple Rain. Its first single “Kiss” was the greatest thing I’d ever heard. I couldn’t get enough. This music taught me to collect. Tape World in the dingy Dartmouth mall offered an endless supply of his 7″s and 12″s, with remixes and B-sides as good as anything on the albums. Each had artwork that complicated the shifting puzzles of his look. Parade was Parisian: black and white photography, clothes cut at oddly revealing angles, lush ferns, and marble. It was all noir vignettes and jazz clusters. I didn’t have to go to Boston or Providence, there were these out-of-this-world presences in my everyday life. I put them on the record player in the chaotic living room of the blue house. The black paisley on the white label spun on its tail. Prince kept making everything change.

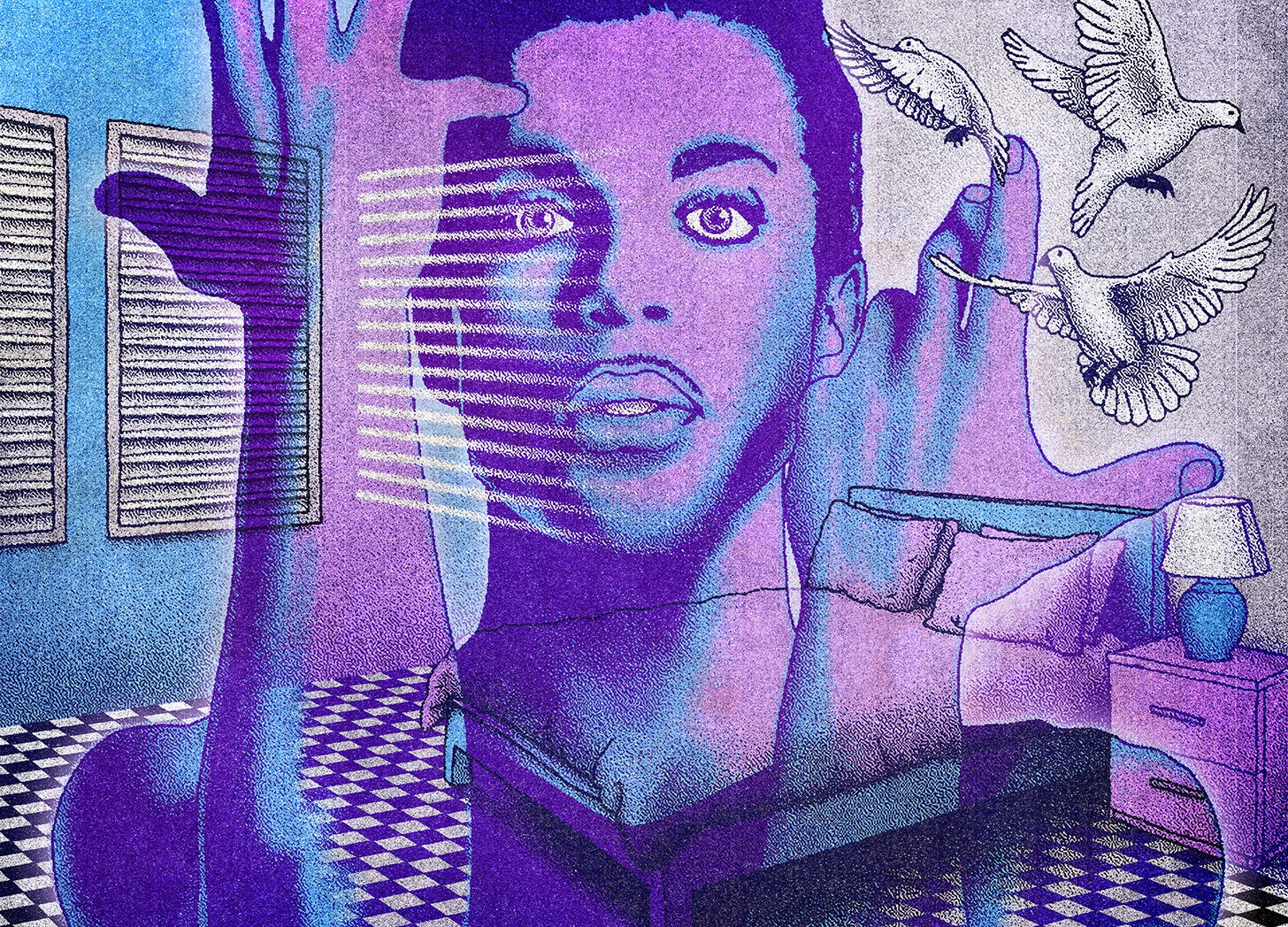

The question of my bedroom arrived. My parents asked me how I wanted it to look. I hadn’t really considered that I could have control over such a thing. There’s a moment on Parade, between tracks two and three on the A-side, where the minimalist but carnivalesque manifesto “New Position” slows itself down, its gated drums skinnying into fingersnaps. An audience laughs or maybe cheers. The song is suddenly the weirdo torch “I Wonder U.” That songs could do this—could recast themselves to become other, related things as you listen—hadn’t occurred to me, either. I stared at the interior gatefold of Parade, a baroque collage of camp clown paintings and band members posing hard in luxurious formalwear. I told my parents, um, something like that.

To my wonder, it became so. My parents figured out how to install vinyl flooring and created a black-and-white checkerboard on the floor. They hung (then) chic white venetian blinds on the long, wide windows; they built a bunkbed so I’d have a secret nook below my sleeping area’s purple sheets. I’d develop a habit of falling out of the bed, but it wasn’t far to the ground. The wall-hung ceramic face mask I’d bought because it looked like the cover of the “When Doves Cry” single—the one with the bright red lips and blue eyes—worked in this bedroom. Which made the new style feel familiar, and right.

I didn’t have many friends, so there wasn’t a worry of what my peers might think of my having such a, well, specific bedroom. At 10, I’d already been fixed on Prince for years, so maybe only its intensity could surprise my parents now. But they liked him, too. And maybe we were all so sad and angry that joy existing was more important than its source. I loved that room. I loved that my parents found the resources to make this world for me, by themselves. It taught me that worlds could be made, to your own taste. Even if it wasn’t easy. Even if you didn’t have much beyond the need to do it. Prince changed every few months. So could I. ⌂