Sticking Your Hand in the Fountain With William Stone

For 50 years, the artist has been making furniture that refuses to behave.

By Lila Allen

When you pull up to the house of William Stone, you’ll know it if you have any familiarity with the sculpture he’s been making for a half-century. At the mouth of the driveway, an inverted, forked tree trunk rises from the grass. Cheap solar garden lights—the kind you can buy at Home Depot for three bucks apiece—stick out from the trunk at all angles, like a mace, or a porcupine, or a maraca-wielding Gumby. You’ve arrived.

Stone has been living here in Germantown, a hamlet in New York’s Hudson Valley, full time since 2020, though he and his wife, Nancy Barber, have owned their house there for much longer. It’s a bohemian spot they’ve carved out for themselves. Stone and Barber each have their own workshops: His for woodworking, hers for ceramics. Creations from both of them pepper the yard and abode, alongside other treasures they’ve collected over a lifetime spent in the arts.

I am here primarily to speak with Stone, whose work I came to know this summer at Available Items, a design gallery in nearby Tivoli. Chad Phillips and Kristin Coleman, its proprietors, organized a solo exhibition called Double Take of Stone’s furniture-sculptures in July. Their shows “tend to focus on things in the domestic sphere,” as Phillips puts it, and Stone’s work fits the bill: For a month or two, most of Available Items’s lower level was filled with chairs, shelving, tables, and other items that the curators pulled from the living archive that makes up Stone and Barber’s home. “He has wall art, 2D art, furniture, cabinets, clocks... everything except a rug,” says Phillips.

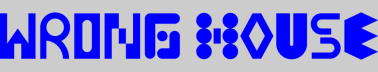

Here in Germantown, Stone and Barber have more or less staged their home as a gallery, too—only, you can, and should, touch everything. (Touching—and sitting—were also welcome at the Available Items show.) Barber’s dimensional, colorful tiles cover the walls, and a dozen or so of Stone’s sculptures hold court in an office overlooking the Hudson River. Many of them are chairs that Stone has Frankensteined: In one, a flotilla of scrap wood arms makes up every component of the chair—legs, seat, back—and in another, four salvaged ladder backs form a barrel-like surround.

Stone has been chopping and screwing like this since the early ’70s, when he shifted his artistic focus from poetry—he studied literature—to sculpture. Over the decades, it’s fair to say he has fused art and life. In the early ’80s, he and Barber ran Tenth Avenue Bar, a restaurant and gallery in a former leather bar (“there were chains hanging from the ceiling, and a tub in the back for golden showers,” says Stone). The Talk of the Town called it “the only place in New York where you can eat herb gnocchi and look at an exhibit called ‘The Bad Light Photography Show.’” In the scheme of the artist’s long career, the restaurant was short-lived—but it showed early on the ways that Stone has cast creative work as something to live with, not just look at. “It’s part of his Fluxus training to disrupt everything,” says Phillips, referring to the late-20th-century, genre-crossing movement that questioned the authority of the art establishment. “Like, it’s not art, but it’s art, but it’s not art.”

Stone applies that disruptive energy to access as much as aesthetics. Around the outside of his workshop, he’s scattered some follies. Among them is a column of black metal drums with a small plaque positioned above the entry portal: “LOW RENT TURRELL.” Step inside, look up, and you’ll see clouds pass across the overhead aperture: a Skyspace for the rest of us. Nearby sits a relic of the Covid era, where two opponents can arm wrestle via mannequin hand from a safe social distance.

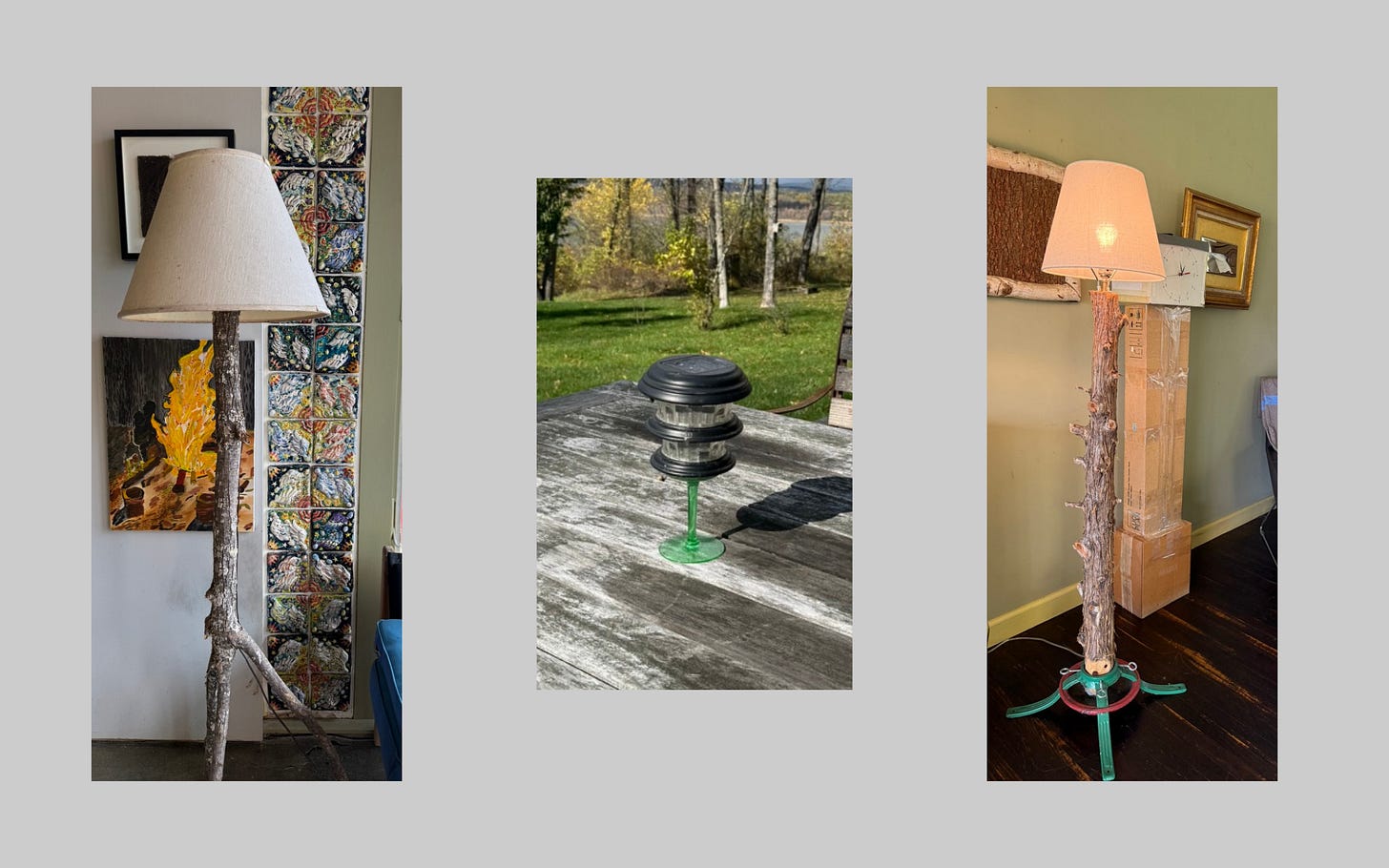

“His pieces are a physical manifestation of his sense of humor,” says Coleman. It’s clear that Stone finds the funny in man’s interaction with the natural world—an interest that started long ago and continues today. An early work of his, still hung in his workshop, presents a particularly sculptural beaver-chewed wood fragment alongside its exact replica in bronze; the day we meet, he’s actively working on a column that marries tree bark with slick veneer, like a 2001 “Monolith” sung in the key of oak. One piece in his living room is the husk of a Christmas tree from years ago; after the holidays ended, Stone turned it into a lamp, incorporating its metal tree stand in the final piece.

As we’re chatting in his gallery-cum-office, Stone dunks his hand in and out of the trough of a fountain he made: Fall Line, a Shaker desk crowned by seven spigots. Each one dribbles water down the wood surface and into a drawer, where Stone is conducting his manual baptism. Available Items’s Coleman pegs this type of casual interaction as part of Stone’s appeal. “Nothing’s too precious,” as she puts it. “But at the same time, everything is so well made.”

As beautiful, and indeed well crafted, as this object is, it’s unsettling seeing water run down a piece of furniture. Stone seems aware of this. We’re looking at it together the same week that the New York City subway flooded—again—from a sudden thunderstorm, sending straphangers wading up to their knees through god-knows-what. It feels like this happens every time it rains more than a drizzle. Like the city is giving way to the ground again. As much as Nature is furious, she’s also inevitable. Stone seems to suggest that the humor lies in our attempts to manage it.

Which is to say: maybe, in being so rigid in our ideas about how things—art, furniture, restaurants, galleries—ought to behave, the joke’s on us. And there’s something compelling about living with objects that don’t pretend to have it all under control, because we never did. ⌂