When the Whole Distorts the Parts

I was looking in mirrors all the time. But was I really seeing myself?

By Madeleine Parsons

Growing up, I spent a lot of time looking in mirrors—rimming my almond-shaped eyes with black kohl, analyzing the size of my pores, turning my face from side to side to determine whether the width of my nose was, as I’d suspected, too wide. I used to wonder if what I saw in the mirror was the same as what everyone saw when they looked at me.

The fact that perception seemed impossible to prove was both maddening and inspiring. I wrote stories about fairies whose reflections didn’t match reality; while their fellow fairies were awestruck by their beauty, the mirror reflected back something dimmer, something secondary and duller. The same way I’d carve potatoes into stamps and press their impressions onto brown paper, and the edges dulled with each press. The sharp stars waning into clouds.

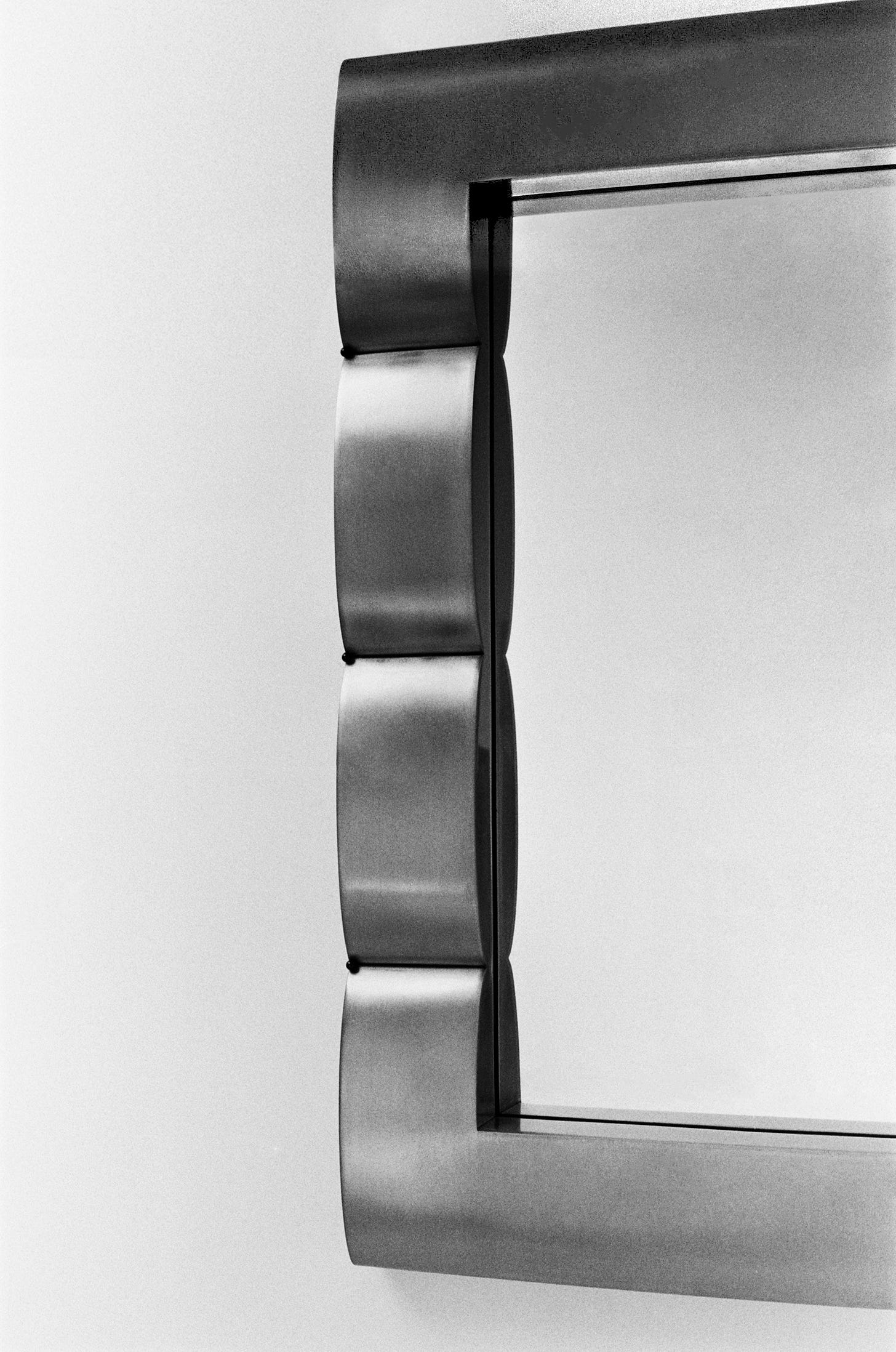

This past spring I was brought to the looking glass more formally when consulting on designer Maggie Pei’s latest collection, Silver Hours, through my work at the gallery Colony in New York City. Her collection developed from the French phrase je me regarde dans le miroir. “I look at myself in the mirror.” In English, we generally phrase this differently, dropping the reflexive: I look into the mirror.

Pei’s understanding of the mirror is expansive—it isn’t just an object, but a liminal space. Both an ornament in its own right and instrument for introspection, her piece Fluted Chambre becomes a poetic threshold where I—standing before it—can exist as both subject and image. I do not just look at the mirror, I look at myself. What I realized in working with Pei was that I was not used to experiencing my reflection as its own actor—until then, it had only been a conduit for understanding the composition others saw of me.

In a high school drawing class, my instructor once advised me to view the face as a series of shapes and shadows rather than a total composition. I was told to focus on the face as skeletal architecture, encased in muscle and tissue. Drawing it—whether it was mine or someone else’s—required flattening that physical structure into something two dimensional. The whole, or at least my perception of it, tends to distort the parts.

In her writings, the mystic-philosopher Simone Weil describes a disconnect between perception and reality. She attributes this disconnect to the false values we’ve assigned objects, submerging them into imaginative perception rather than reality. “Illusions about the things of this world do not concern their existence but their value,” Weil writes. To me, her analysis conjures the more clinical diagnosis of body dysmorphia—a condition where self-perceived flaws in appearance, unnoticeable to peers, become an obsessive line of thought. In my childhood stories, the fairies’ reflections didn’t match their realities because they had become clouded by imagination, doubt, and fear of judgment.

Weil writes that the only way to see things in their naked reality is through a renouncement of our sense of self. For her, true perception means seeing a landscape as it exists when she is not around to see it. But the question, then, is how am I to perceive myself? My reflection does not exist without the medium of a mirror, nor does it exist without me there to see it. But driving upstate recently, I found myself thinking about the line in my side-view reflectors: objects in the mirror are closer than they appear. What if they are actually different than they appear? And what if I am, too?

If I could regard myself merely as subject, as Pei’s Fluted Chambre proposed, then perhaps I could come closer to glimpsing reality. In the light of day, it is still difficult to strip my reflection down to the series of shapes and shadows it is composed of. But catching a glimpse of my reflection at night, I come close, seeing a volumetric flash of cheekbone, a glint of iris underneath a horizontal blur of lash. The disorientation of the dark is enough to wipe away the values I have prescribed those shapes, and separate them from the reality of their reflection. Maybe, with more attention to detail and less attachment to its perception, I can begin to see myself in the light as well. ⌂

Madeleine Parsons is a writer and designer based in Brooklyn. She is an MFA candidate at Hunter College, an art director at Colony, and an adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design.

Not to be too literal about it but this brings up for me the distortion that we have lived with for centuries as mirrors reverse images. So the me in the mirror is not the me seen by others.

Beautiful, beautiful. Didn't know of Simone's work before reading this - love it all.