The Fog in Pristina

I stumbled through Kosovo’s capital in a cloud of grief and drink, looking for a renewal. All that I found there were ghosts.

By Matt Cosper

In 2011, I quit my job at the book warehouse because Bek invited me to come work on a play with him in Pristina. My parents had died unexpectedly and quite suddenly that year and I was deep in a haze of grief. My mother in May and my father in August. I was living with my brother, his wife, and their infant son in the Pacific Northwest. I don’t know if I realized just how heavily I was drinking. Even if I did, who was I to argue with family tradition?

Although my life as an alcoholic warehouse hump was stimulating and glamorous, I jumped at the opportunity to work as a director again. I’d be workshopping an Albanian translation of Strindberg’s Miss Julie, with Bek playing the role of Jean in the production and serving as my translator for the production process.

My grandmother was so angry with me for quitting the book warehouse job that she sent me a scathing letter in the mail. I discarded it unopened because she called me ahead of its arrival to apologize and ask me not to read it. She’d always been so sweet to me and I preferred to keep that perspective intact. I honored her wishes and trashed the letter unopened and unread. On the phone I lied to her and said that the money I’d be paid for the gig was good and that this would be very helpful for my theater career. I didn’t think I was lying entirely. Just enough to get her off my back, and maybe even impress her a little.

The night I arrived in Pristina, Bek took me to a small movie theater to see a local film about a Kosovar national hero. From his description I couldn’t tell if the movie had been made by one of Bekim’s dearest friends or a bitter rival. Whatever the case, the whole evening seemed to be unfolding in a spirit of chaotic good fun and I went meekly along for the ride. We waited in line on an icy street. It was February and bitter cold. I was underdressed and felt like an urchin in some Victorian social novel. When we got inside and someone handed me a massive beer I murmured my gratitude obscenely.

The theater was packed and noisy, and I wasn’t sure if they loved the film or hated it. More likely they loved hating it. It was warm and dark, womblike, in the theater and I was very nearly asleep for most of the film. Occasionally I would jolt back to awareness, confronted by towering images of mustachioed men in fur caps and peasant blouses waving swords at me. The room shook with laughter and conversation that I had no way of understanding.

My memories of Pristina are suffused with fog. Everything was overwhelmingly vague. I was so profoundly jet lagged, and it lasted the whole time. Perhaps I was being drugged? I’ve never had jet lag last that long. For weeks it lingered. I was drinking Raki, a strong local liquor, while I was there, but I’m a grizzled enough old libertine to know the difference between drunkenness and whatever this was. Perhaps I was being drugged? Who would want to drug little old me?

Each morning I would wake and walk down to breakfast. The hotel that Bek had put me up in was nice but because it was either new, being renovated, or both, the elevators were out. I was only on the third floor so it wasn’t a bad walk down the broad staircases. The staircases were carpeted in lush pile but the walls were all covered in large sheets of plastic. Through the plastic I could make out the general forms of sconces and large oil paintings. The paintings seemed to be landscapes or historical scenes but I couldn’t be sure. I was looking at them through a veil of nearly opaque plastic. The plastic sheeting and the thick carpets did strange things to the sound. In the mornings I often feared I might be going deaf.

I seemed to be the only guest staying there and my breakfasts were lavish but lonely. A full buffet was laid out each morning. Sausages and burek and eggs and fruit. Piles of meat and bread. Very good coffee. I sat at a different table each morning as a sort of game I played with myself. I sat alone and ate great mountains of burek with rich coffee and steamed milk. The tablecloths were substantial and the china fine. It was an upscale joint and I was all alone. I never saw another soul at breakfast. I felt like a prince in a lesser-known fairy tale.

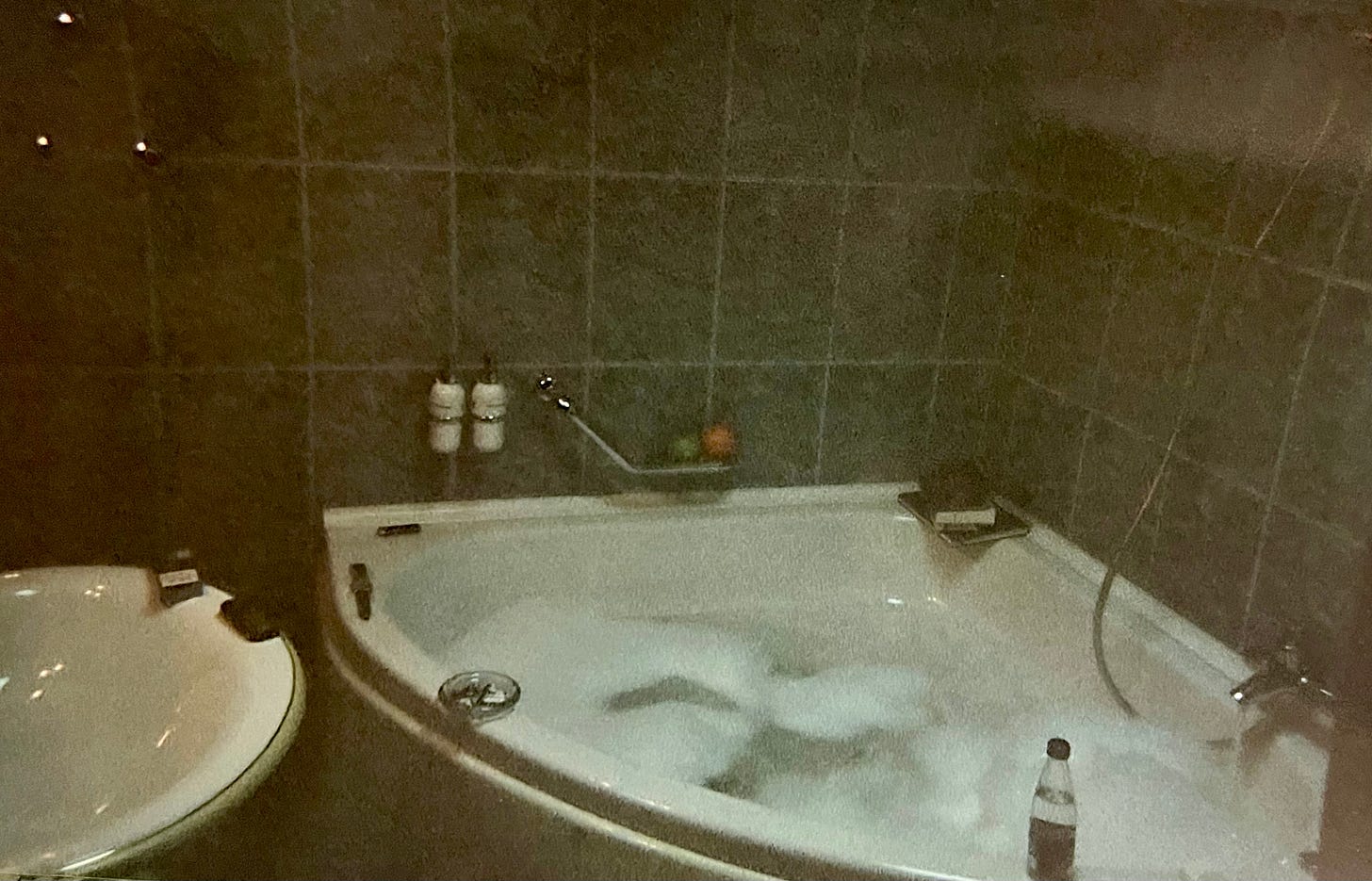

After breakfast I would climb back up to my room for a bath. I was reading Kaputt, Curzio Malaparte’s surreal dispatches from WWII’s Eastern Front. I’d loll in the bath for a couple of hours, reading and smoking. I’d scrub myself vigorously. Occasionally I’d make some notes on the play we were supposed to be working on. I wasn’t sure how to navigate Strindberg’s corrosive misogyny without completely reimagining his play. It’s a tricky thing, to navigate a dead man’s work. Especially someone like “Mad Gus” Strindberg, author of The Occult Diary, who is liable to come and haunt you.

Every day I’d leave the hotel around three in the afternoon. I’d meet Bek for macchiato and discuss that day’s rehearsal. We’d listen to Roma musicians playing outside of cafes and talk about incorporating their music into our performance. These were the best parts of the day. One funny thing about these afternoon appointments: every day as I was leaving what seemed like a deserted hotel, an armada of limousines would be pulling up to the front. Some of the long black sedans had little flags flying from the fronts of them, mounted just above the headlights. In my haze I’d stumble past them, muttering at the giant men getting out of the front seats with automatic weapons strapped to their chests.

One day Bek took me on a drive down through the Šar mountains, and we ended up in Prizren in the late afternoon. The drive took us up and then down the mountain, winding through thick fog. Everything was dreamy, the scenery emerging only in faint glimpses now and again. Black trees like lightning bolts mostly. Sometimes the tower of some old ruined fort. Bek, ever the spokesman, kept a running commentary the whole time. I was glazed over. He might as well have been driving a dressmaker’s doll to Prizren. One that chain smoked and wondered where his parents had gone to now that they were dead.

Prizren is all medieval and late antique charm compared to the hustle, bustle, and gloomy utilitarian architecture of Pristina. We ate doner kabobs by the river and I had my picture taken in front of a very old mosque. Bek acquired some small reliquary figures which were then stashed in a compartment in the front left wheel well of his car. They looked unspeakably old. He let me hold one, a simple stone figure like a dog. It smelled like rain and made me want to somehow burrow deep inside of it. Its density, its heft, made time seem silly and it made me want to sleep for thousands of years. A sleep like that might cure me. I’d feel much better then.

I went to see a play while I was in Pristina. A production of Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden. The play was staged in the vast cavern of the main auditorium of the National Theatre. The audience was led through the dark and up onto the stage to sit in a circle around the performers. Early on in the play an actor pulled out a gun. Having seen my fair share of theatrical firearms it was immediately clear that this was a real pistol. I was concerned and for that I was grateful. At least this was something cutting through my haze. I was keenly aware of my heart in my chest. That it could stop beating at any time. Why was it beating so fast? When they started shooting I thanked God for the terror surging through me. Afterwards I was ravenous.

I remember the food. My friend took me to a series of fabulous restaurants that appeared to be private clubs. Tiny structures of wood and stone hidden down some alley and always a locked door. Bek would knock confidently and we would wait. The door would open a crack and cautiously blank faces opened into warm smiles upon seeing Bek. We’d be ushered into cozy rooms that smelled like heaven and sat at a table that began to fill with small plates of meat and root vegetables, cheese, and bread, red wine and always more shots of Raki. At the first restaurant we went to I noticed two men who looked distinctly American sitting in a back corner. They wore dark suits and, no joke, sunglasses. Sunglasses in a dark room at midnight. As I became drunk on food and wine I ignored them. In the morning I couldn’t remember getting back to my hotel.

The next time I saw these men, we were at another private restaurant. This one was owned by the son of the owner of the previous joint. This one felt more modest and more modern. A little less like a fairy tale. The food was just as good though and there was the same insistence that I drink inhuman amounts of Raki. I remember wondering if there was some etiquette I was fumbling; if I was somehow to blame for how much we were drinking. If only someone had told me the secret password I would have said it. I was beginning to have trouble keeping it all together. My hands trembled when I lit my cigarettes.

That night the men in suits and sunglasses came and sat at our table. I was of course too drunk to know what was going on but these men seemed very nice.

“Swell couple of guys,” I thought.

Bek and his friends kept teasing these men about being spies. They referred to them as spooks and eventually they were explicitly referencing the CIA. The men in question remained good natured in the face of this. They smiled and laughed and shook their heads. We had the wrong idea, they insisted. They were mere security consultants.

Did I mention the jet lag? This was more intense and drawn out than any I have suffered before or since. I never acclimated. At night I tossed and turned only sleeping fitfully and during the day I either soaked in the tub buzzing like a broken radio or I wandered Pristina like a zombie. In rehearsals I relied heavily on Bek, as my translator, to render my monosyllabic groans as actionable directions for the actors.

I remember one morning when I finally fell asleep at sunrise. I was asleep deeply but only briefly when I sat up suddenly awake and aware of my father, now six months dead, standing at the foot of my bed. He looked down at me with sadness and disbelief. “This is all bullshit,” he said before fading away. I skipped breakfast that morning. I lit a cigarette and ran a bath instead. I wasn’t sure what dad meant. Was he reporting back on the afterlife? Was he angry, like grandma, that I’d quit my job to come drink with spies in Eastern Europe?

The next day after my visit from the ghost of my father, Bek informed me that our project was canceled. The government, which had been favorable to him and his theater company, had been overthrown. He didn’t have friends in the new mob and so the money had been turned off. Apparently the coup had been planned in the very hotel I’d been staying in. He had a plane ticket for me and I’d be heading back to the states early the next day. He’d even been so kind as to have the hotel staff pack my bags for me. ⌂

Matt Cosper is a playwright, poet and critic who lives and works in Charlotte, North Carolina. Someone should publish his debut novel, Idle Hands. It is quite good.

Editor’s Note: This essay is a work of creative nonfiction. Names, events, and certain details have been altered or fictionalized.

This whole story feels like a dream