The Restorative Magic of Nigerian Souvenirs

Thoughts on the stamped and screen-printed mementos that punctuate Nigerian life.

By Ekemini Ekpo

I’m coping through athletics because physical sources of comfort are scarce. My family is dispersed between Africa and North America. My favorite Nigerian comfort food is out of reach; I can’t do much with the Baby’s First Afang Soup kit that my mom gave me without palm oil, a more-than-necessary ingredient which is mostly only sold in specialty West African markets.

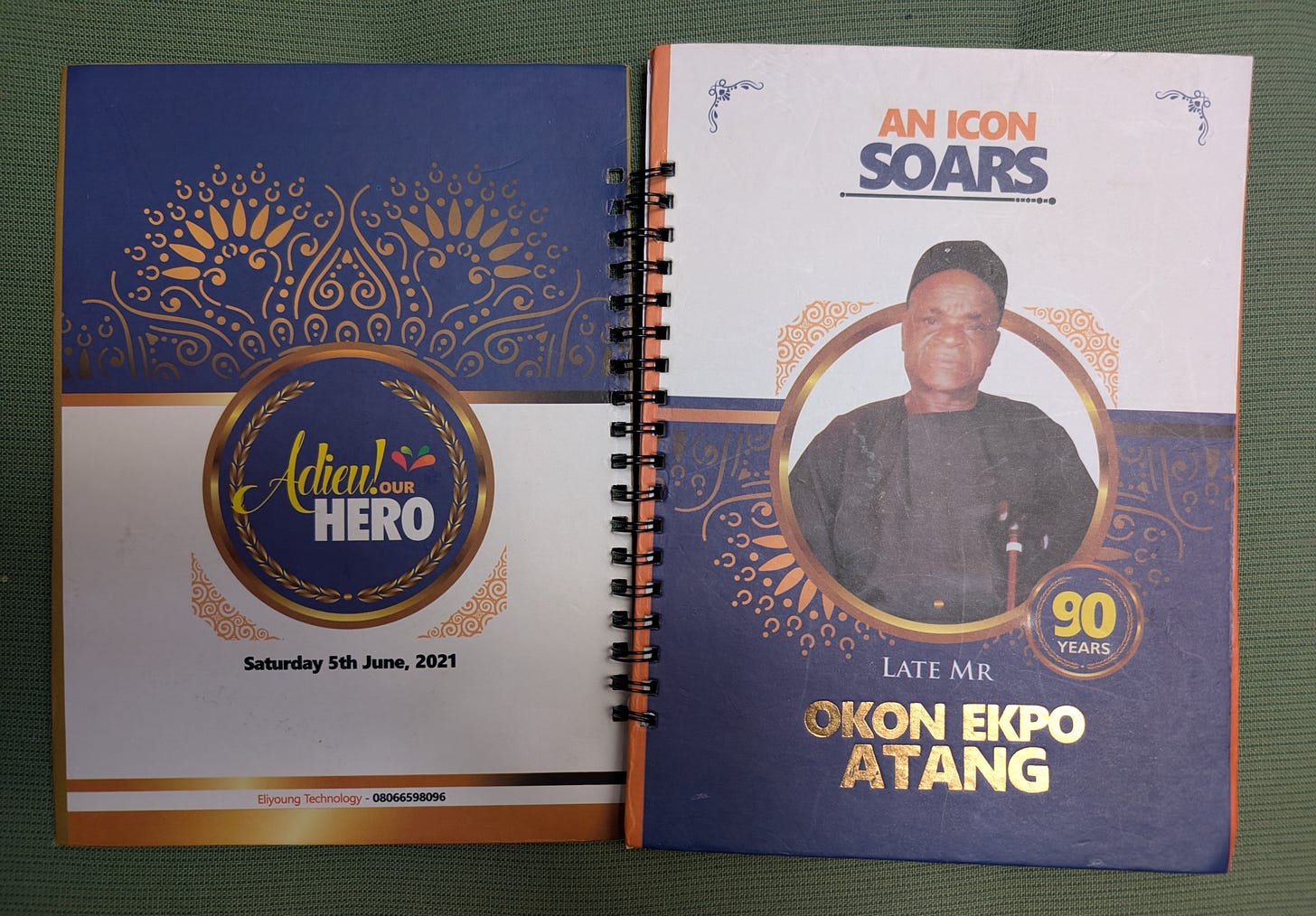

Right now, it’s just me and my limited-edition funerary notebook against the world. My parents gave me the notebook upon returning from my grandpa’s burial in Nigeria; it’s a bit of a consolation prize, to be honest—my siblings and I “attended” by watching grainy livestreams.

The front cover reads “AN ICON SOARS / Late Mr Okon Ekpo Atang / 90 YEARS” and features a photograph of my paternal grandfather. The back is the inverse of the front, with a few alterations, the most significant of which is a replacement of the photo with a written goodbye: “Adieu! OUR HERO.” Every page inside the notebook itself features the copy from the covers. Scribblings fill some pages; others contain frantic handwriting—repeated sentences I jotted down when I was learning lines for an acting gig. Most pages have been torn out, their fate lost to history.

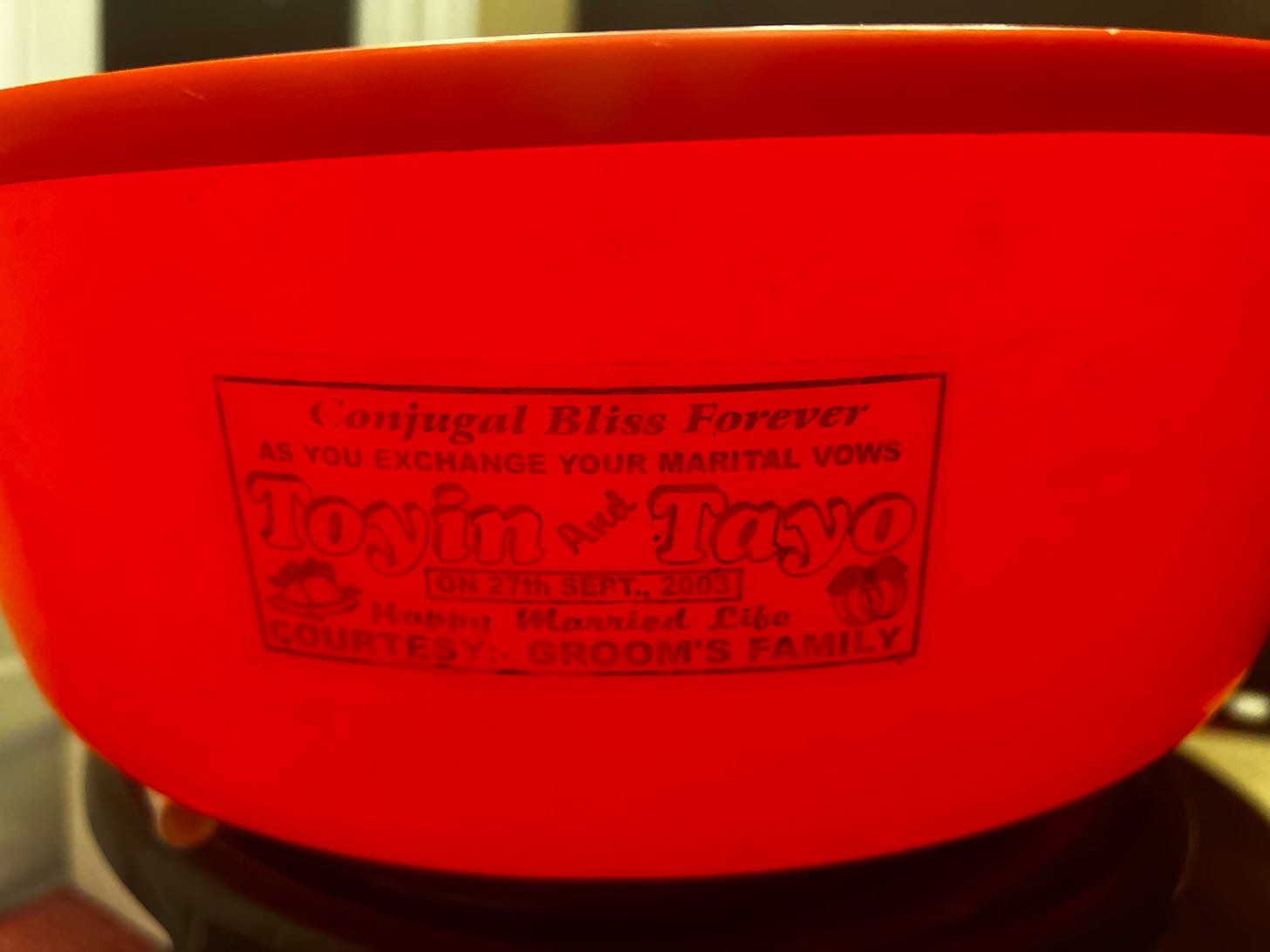

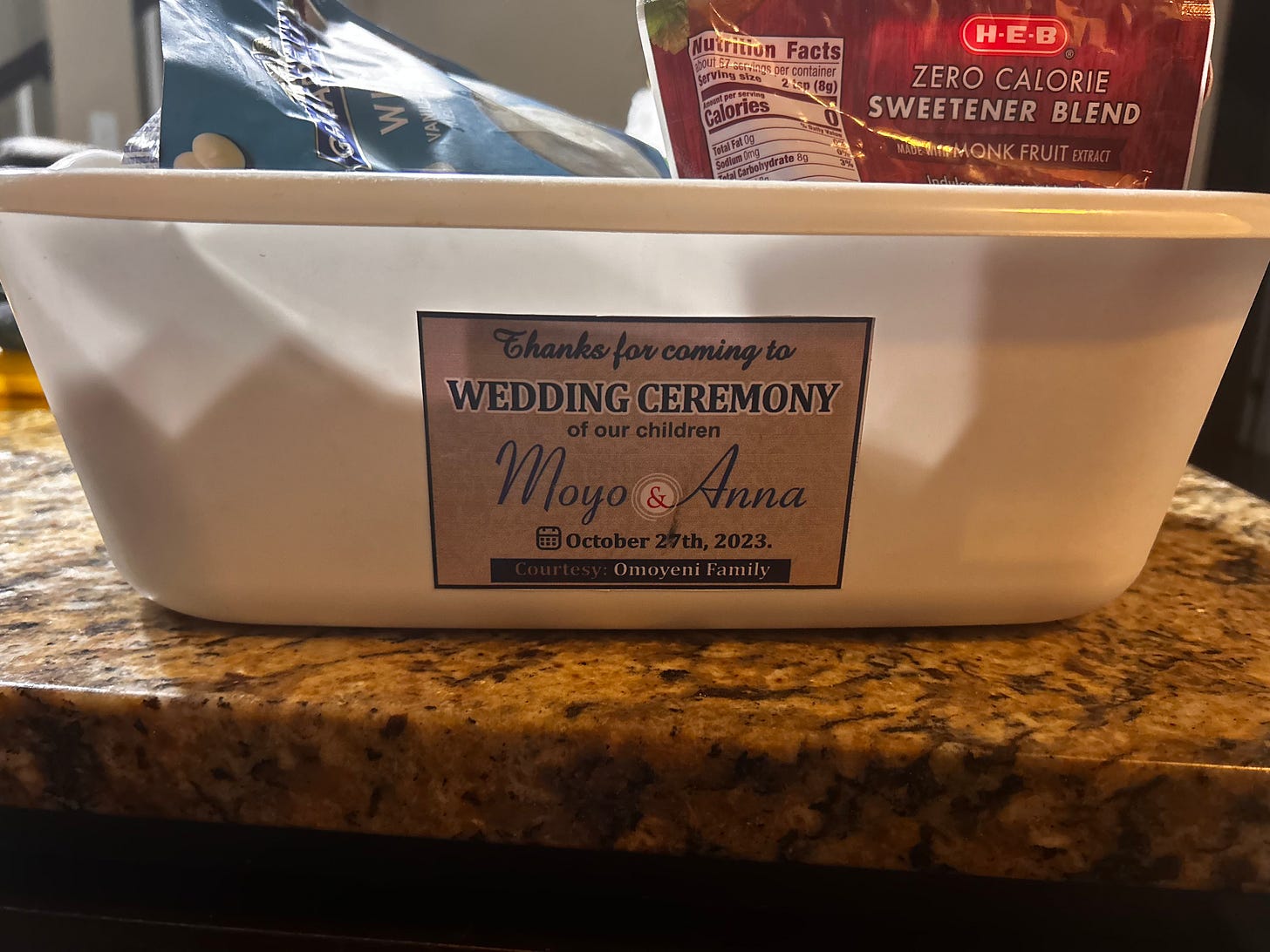

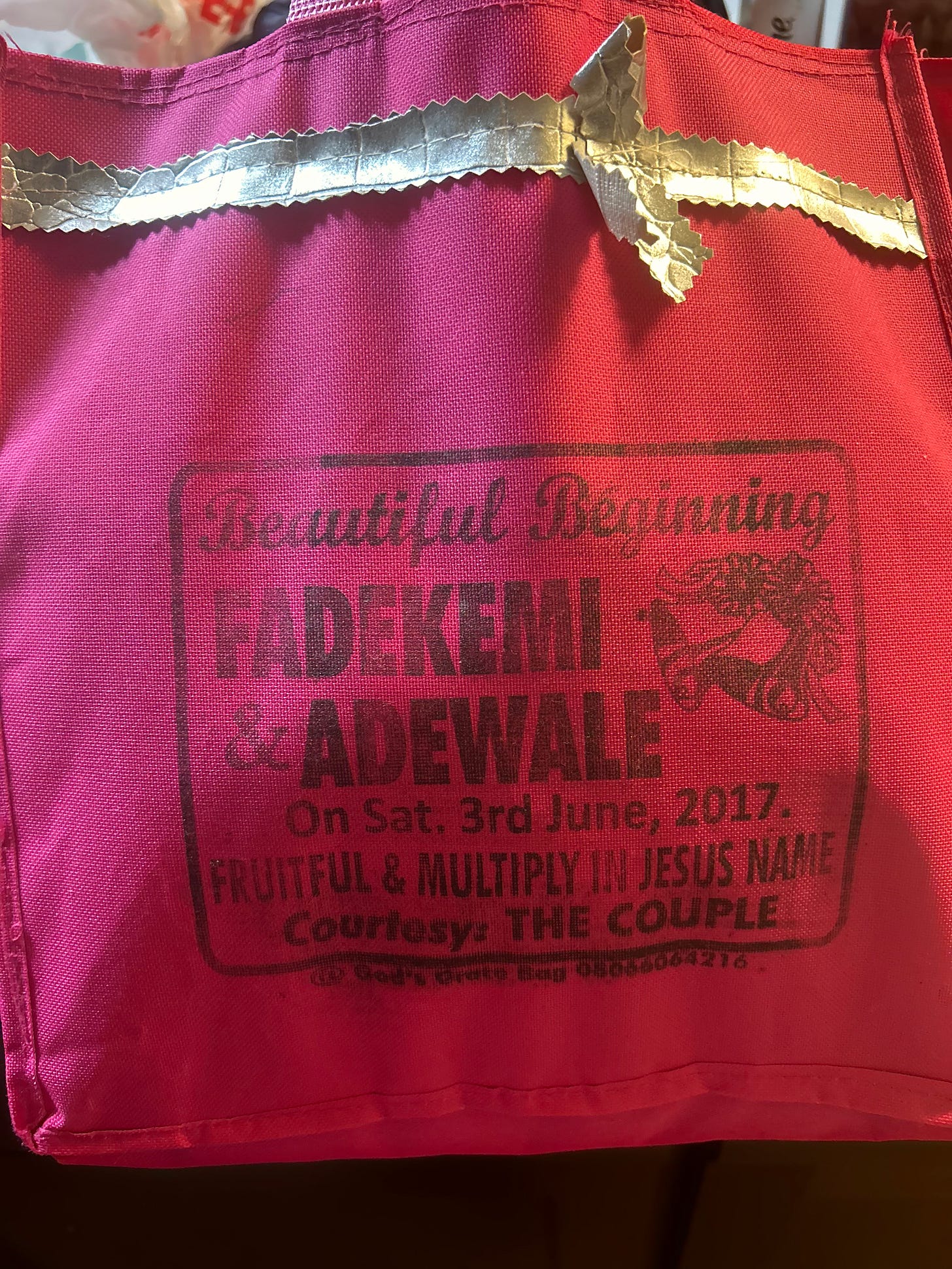

It’s common for a sentimental object to also be useful—Grandmamá’s cane or the family fine china are proof of that. But it’s more of a rarity, at least in America, that useful objects overtly announce their sentimentality. Not so in Nigeria or within its diaspora. Every Nigerian I’ve ever met could tell a story about how they attended a special event—usually a wedding, funeral, graduation, or birthday—and left with a practical, personalized, “ICON SOARS”-like doodad as a party favor. Buckets, pens, journals, keychains, towels of varying sizes, cooking implements, the kitchen sink.

On a base level, it’s not surprising that this practice has taken root within a culture that conflates respectability with respectfulness: “Oldest daughters do this, oldest sons do that.” “Only use this hand.” “Prostrate for your elders.” The obligatory performance of politesse is one of only a few tenets that unites a country with over 250 ethnic groups. You cannot invite someone to your party and send them home empty-handed, just as you cannot invite someone to your home and not have food for them to eat. And in this culture, the fine print states that the party favor needs to be substantial, just as the food needs to be satisfying (Charcuterie boards and “lite bites” won’t cut it in Nigeria.)

And with performance comes competition. The party hall is the auntie and the Ọ̀gá’s soccer pitch. In some instances, party guests have gone home with new cars, iPhones, and petrol for their automobiles. I’ve personally heard reports of air fryers as souvenirs. Ostentation is another Nigerian virtue, and clout is currency. Are you rich enough to buy an iPhone for dozens of people? Were you invited to the party where they raffled a Toyota?

Rich folks’ antics are not the purview of regular people, but even the most modest party favor is engaged in a psychological, if not sociological, battle. By giving out objects that guests are likely to revisit, the benefactor stakes a claim on the attendees’ memories. If Ndianabasi and Eghonghon gave out the wedding cheese grater that people really like to use, then their nuptials will always be top of mind—at least until the ink has washed away, and it becomes just another kitchen tool.

If and when that happens—sorry, Ndianabasi and Eghonghon—what’s left is an ethos of love, unmediated by the self-serving impulse to take credit. These are functional objects: A calendar helps you measure the passage of time; an umbrella shelters you from the rain; a notebook helps you learn your lines. These party favors, if properly considered, improve your loved one’s lives. They are a way of saying, “You took care of me by showing up at this important moment—let me, in turn, take care of you.” They are tender—not because of nostalgic affect, but because they are an expression of care in and of themselves.

For what it’s worth, even though I know neither an Ndianabasi nor an Eghonghon, the cheese grater actually exists. Right about now, such a cheese grater sits in the pantry of my family home, a souvenir from the burial of my maternal grandfather over a decade ago. The ink has long since rubbed off, and its structural integrity is partially compromised. I don’t see it going anywhere, though. It’s taken care of us for a while now. It still has its uses. ⌂