Salvaged Light

A collaged conversation on illumination, craft, and material afterlife

By Emily R. Pellerin with Seth Caplan

Prologue

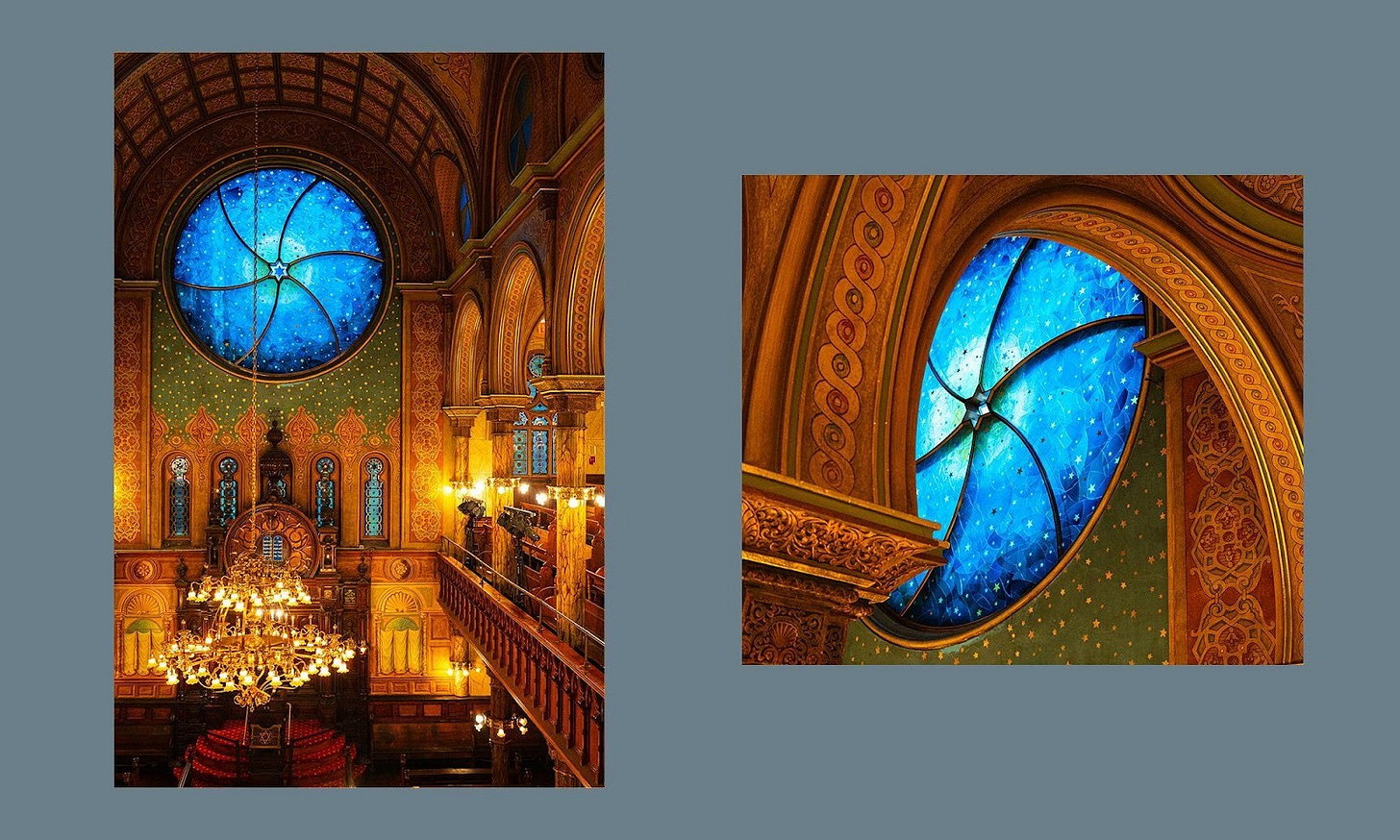

The sun dips so quickly in the wintertime. In the dusk, I don’t feel like I’m giving this stained-glass behemoth its proper viewing. Even so, its brilliance has me sucked in.

It’s late afternoon and I’m at the Eldridge Street Synagogue in New York City, on a balcony above the sanctuary’s pulpit, staring up at the circular, cobalt-colored East Window. Contemporary in an otherwise historically preserved 19th-century sanctuary, the engulfing piece is 16 feet across, twinkling with a near-white interior circle and a receding deeper-hued perimeter. There’s a smattering of tiny metallic stars around the edges. The piece is a mesmerizing manipulation of light—light doing things I’m not used to seeing it do.

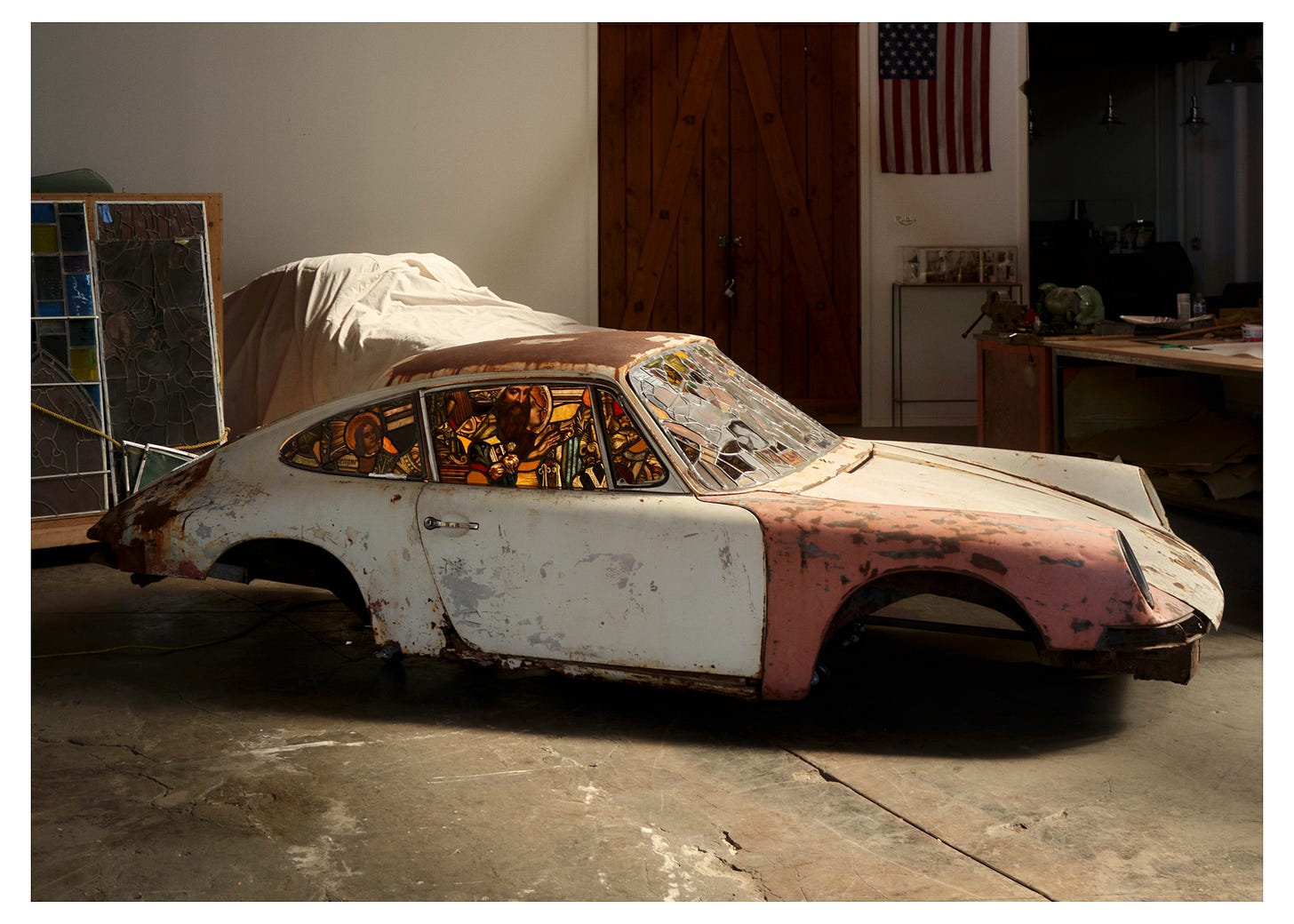

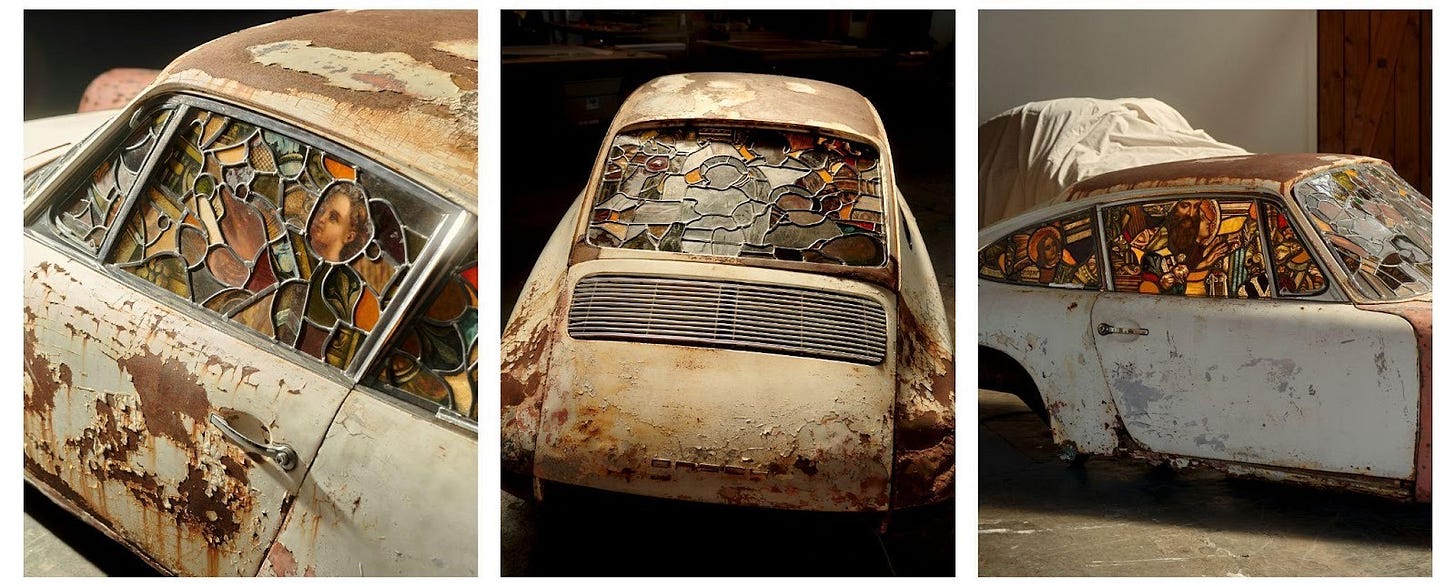

Back in July, photographer Seth Caplan also followed the light. And he too found it doing things he wasn’t used to seeing it do. He saw it peeking through the windows of derelict vintage Porsche cars, where devotional stained glass took the place of transparency—the work of LA glass artist Ben Tuna, who runs Glass Visions Studio out of a garage in Glendale.

Inspired by Seth’s photos of his studio visit, I set out on a tandem journey to explore the practice of stained glass art, and the unexpected cult-car-art project Seth had turned me onto. What followed was a series of conversations with experts, historians, and practitioners of related disciplines, all sourced based on an instinct that they could shine light on the subject matter—its history, work, industry, and art.

Accompanied by archival and contemporary images of stained glass, these conversations have been crafted into an asynchronous dialog that contextualizes a century-plus-old practice in light of Ben’s art-cars.

PART 1 : CARS

MOSES NNADO1

Ferdinand Porsche designed the original 911 model. He had the mindset of a sculptor. He said he wanted the car to look fast, even when it wasn’t moving. I can attest to that: Standing still, it looks like it’s moving. It’s a design heritage that they haven’t really strayed from for the past 60-plus years—decades down the road, the cars share the same DNA.

BEN TUNA2

I grew up loving cars. I used to make my mom pull over if we saw a construction site so I could look at the tractors. Now I have classic cars, and look at cars online all the time. Last July, I saw a shell of a ’69 Porsche 911 in Ohio. I didn’t need it, and didn’t know what I was going to do with it. No windows, no floor, no engine, no wheels. I called the guy and bought it. So I had this big rusty shell of a car.

Then I came across a guy in the Palisades who, after the fires, needed his lot cleared. He had a collection of four classic cars that all got burned. He used to go on dates with his wife in the car; he used to take his kids to the beach. We dragged them out of the ashes in the guy’s garage.

SETH CAPLAN3

Cars are a sexy thing. I don’t think of stained-glass windows as sexy, per se, but they have a definite mystical energy. When we think of a Porsche car, in general, we think of good design and artistry. It’s an art object by nature. Sexy or not sexy, all these elements have a history, an aura. The marriage there is exciting.

MOSES

The Porsche 911 found a lot of its shape in wind tunnels, in testing in the early ’60s, to really leverage the aerodynamics. It is inspired by sculpture, not just engineering.

PART 2 : LIGHT & SPACE

SETH

Similar to the way clerestory windows are in churches, a similar quality was happening in Ben’s studio when I visited. It has a beautiful skylight, an arched ceiling, a lot of direct, California sun illuminating the different panels and colors, and gorgeous wood in the roof architecture. I was interested in the space itself. And I’m always interested in light, and how to use it to tell a story.

DIANE C. WRIGHT4

When you’re talking about stained glass—which started out as an architectural element—natural light becomes really important. It changes the way you see the work over the course of a day. Seeing windows at a different time of the day changes your experience. It makes it living—dynamic as an object, instead of one that always looks the same.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER5

The first High Gothic stained glass starts around 1200 or 1300 in France, with Saint-Denis Cathedral. This is when they figured out how to make groin vaults and flying buttresses and Gothic vault windows. That allowed the architects to basically empty out the walls. They’d figured out clever engineering, so that’s when they started filling the churches with stained glass.

REVEREND DAVID WANTLAND6

In a church, the direction of the light matters. Obviously the thought is, you’re inside church, so at some point in the day, the daylight is lighting the stained glass window. It’s only for the people on the inside.

Yet it’s only at night, when lights are on inside the church, that stained glass is illuminated for everyone else, for those on the outside. Who are we trying to shine light for? Is it just for the people that are already here? Or are we looking to shine light out onto the world?

BEN

I make the [car] collages on a dark wood table, so you don’t know what the light is going to be like when they’re all installed. It’s freestyle. I know what I’m putting into it, but I don’t know what it’s going to look like altogether. There’s weird, beautiful “oopses.”

DIANE

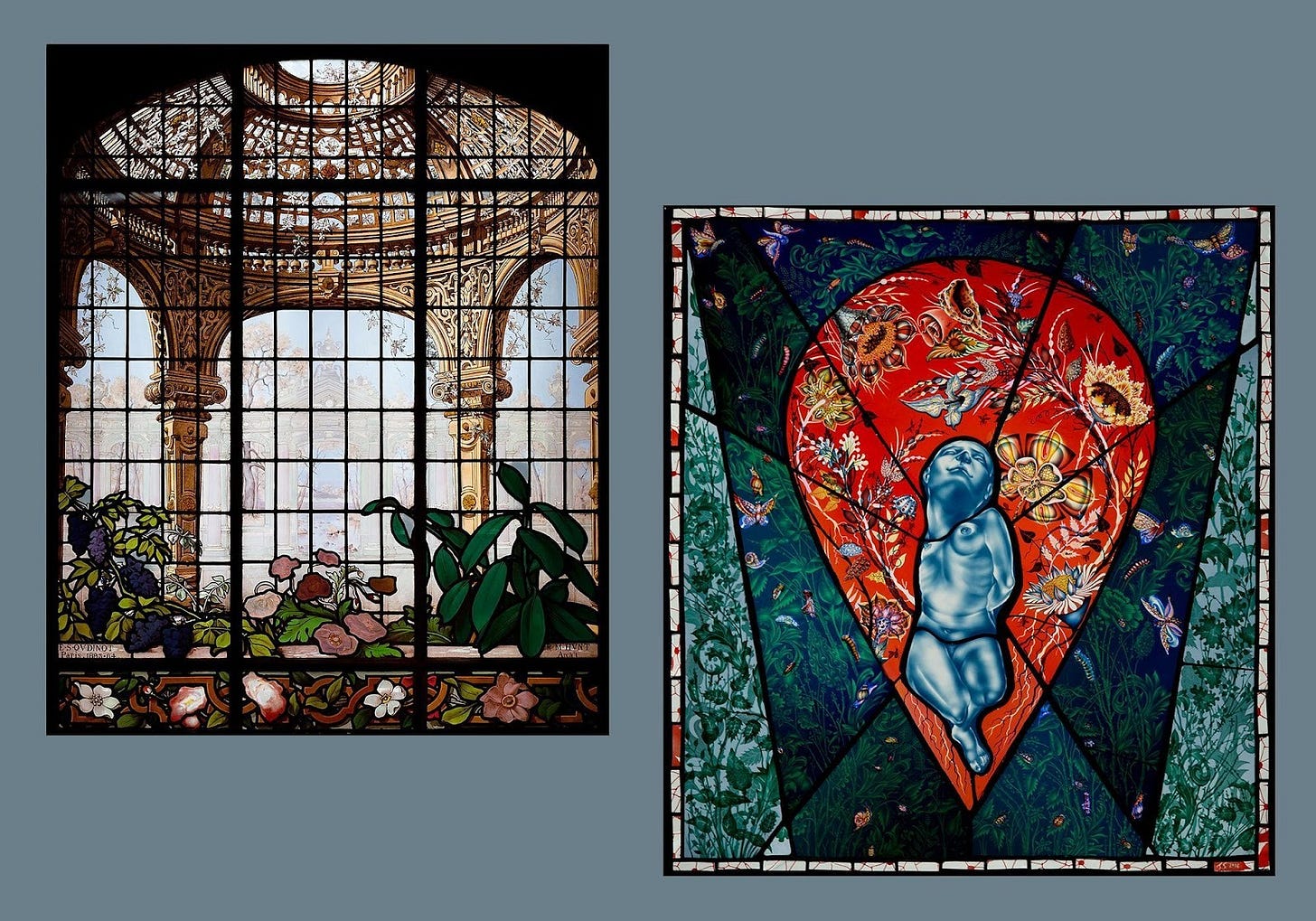

In some of the earliest stained glass, there was a really limited, certain color palette that was being used. Jewel-tones, primary colors, blues and reds and greens. Fast forward to the 20th century, particularly in England. They were looking at medieval and Gothic architecture, and reviving the past.

Over in the United States, this guy Louis Comfort Tiffany becomes very interested in glass. But he decides that instead of painting on the glass, he’s going to make pictorial windows—but all the color and texture is going to come from the glass itself. That was a huge innovation in glass.

BEN

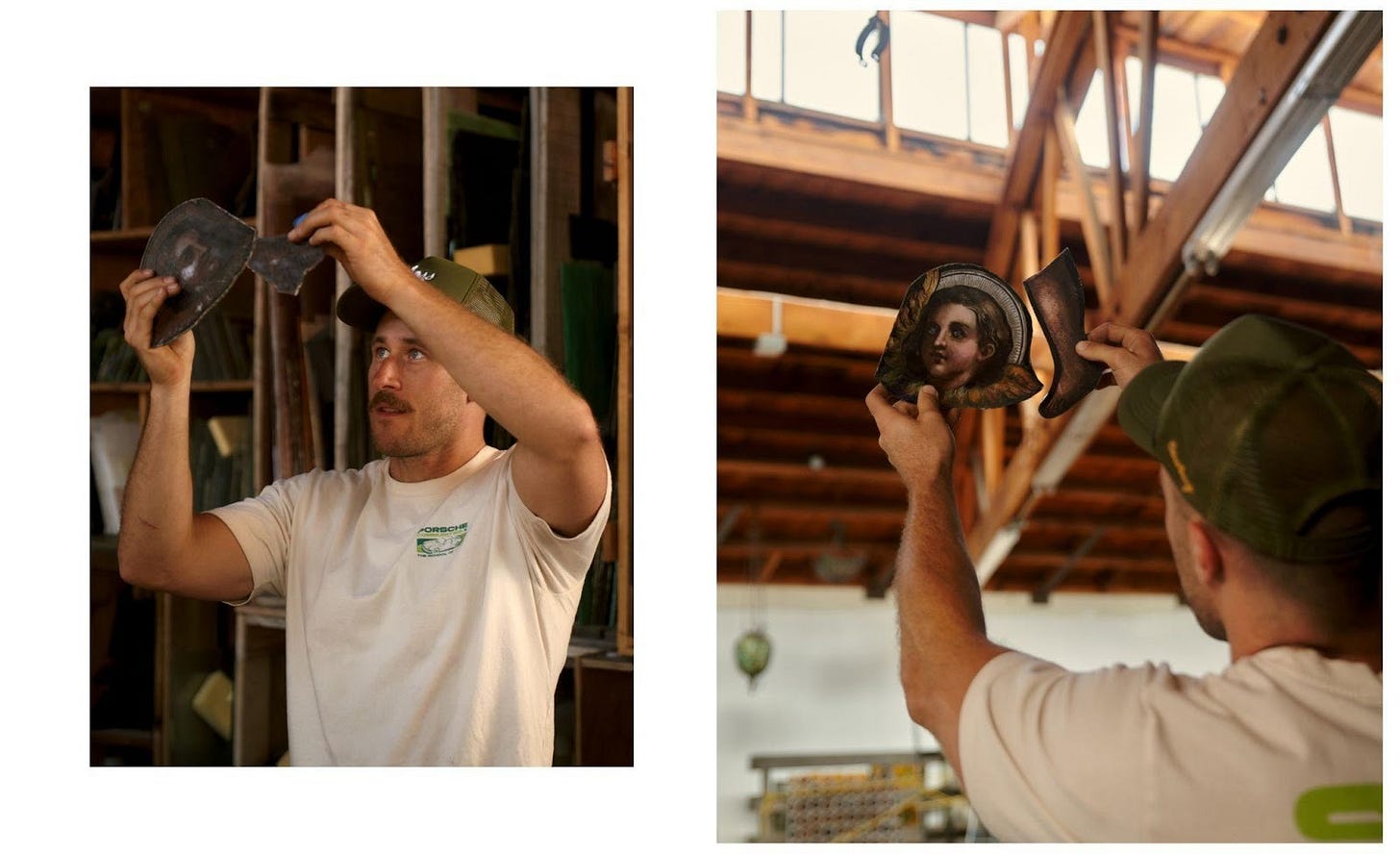

I grew up in historical restoration, doing what the client wants. But I am interested in exploring the medium now, and seeing where I can push it. For the glass in the cars, we take [salvaged church] windows apart, then we catalog all the pieces [by theme, based on what they’re depicting,] such as “floral” or “feet”—and then we rebuild. One windshield of a car might have seven different churches’ glass in it. I make templates of these windows and create a mold to fit within the windshield, and I put thousands of pieces of glass on the table. Then I just start building.

SETH

Ben’s studio is stunning. There’s a dreamy quality to it, with the car installed in the middle of this huge space, and the stories of all of the elements mixing together—the patina of the car body, the repurposed glass, and the studio’s own industrial past.7

PART 3 : LABOR

BEN

Glass is a very “pushable” medium; it’s very versatile. It’s not just a trade, it’s an art form that can be applied in so many ways. The people working [in stained glass] are master artists.

DAVID

I think about how stained glass was primarily pitched as a catechetical tool, a way to teach people about the faith. Imagine a mostly illiterate society: The stained glass would be a way to [illustrate] oral traditions. I think about it less as an inherently spiritual or religious component to space, but as something that anyone can use who’s trying to teach non-written, deep meaning. It can contain a lot of layers.

BEN

My project has become a push to shed light on this craft. It is a fine balance between labor and art, a balance of fineness and grit. There’s a lot of studying and design work, then there’s the dirty aspect of ripping stuff out—rebuilding and breaking and trashing.

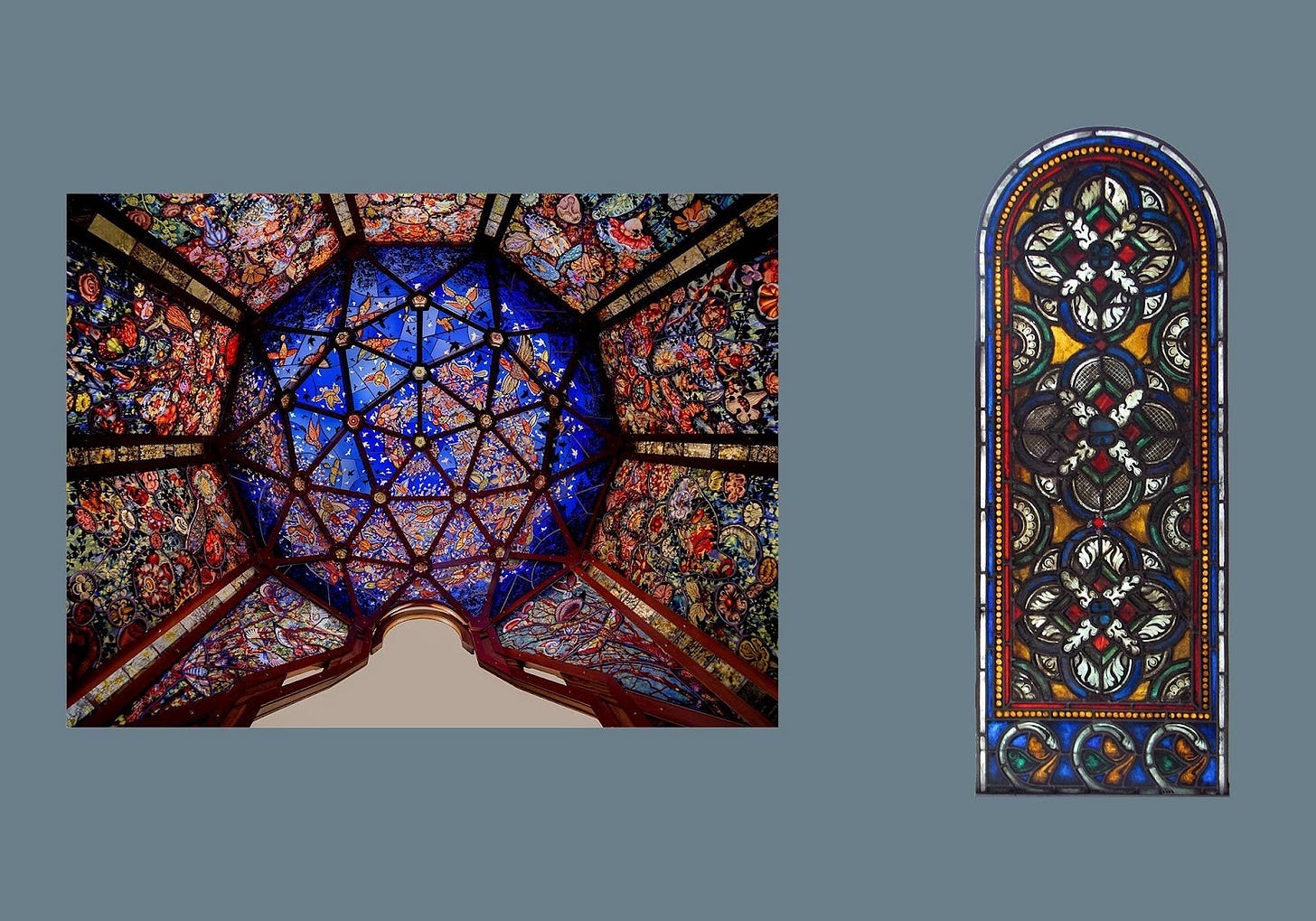

JUDITH

I’m inspired by the glass itself. I wanted to make something emphatically crafty.8 I was trying to make a statement about the value of DIY. In that, there was an element of wanting to suffer to make that thing. Suffering is an important part of art-making—people don’t want to admit that. I wanted to labor over it.

BEN

You have to go super tight and really small, and draw a scale drawing—and figure out how to blow it up to full size. You’re talking about a 16th of an inch. If you mess it up, you have to start over. When you break a piece of glass wrong, you throw it away and start a new piece. It’s the most unforgiving medium out there.

DIANE

Artists who used to work [in this medium] would have workshops. Decorating, cutting, image creation, soldering, and leading. It’s very labor-intensive.

The type of glass that Tiffany was making was so dramatically different from antique glass. He’s getting all these textures and colors that they’re making these incredible pictures out of. In Tiffany’s shop they had a women’s department—a very distinct division where he had all the women picking the glass out, and the men would do the soldering. He thought the women were probably better at picking out the colors.

BEN

Glass teaches you immense patience. When you work with a medium this frustrating, because you can break it so easily, you’re also cutting yourself constantly. Your hands are cut up, your fingertips are sore. There’s an immense physical element.

DIANE

When you have all the glass laid out in its final shape and form, then the lead comes in. It’s what holds the windows together. The lead has little channels, and you slide the glass into the channels and you solder it. The lead is soft; it’s a little bit flexible. Now you have this big window, with all these little pieces of glass, like a puzzle, and the whole thing has this interesting flexibility to it.

This plays into the character of glass: The glass is so fragile, but you have to think about these windows that have survived for centuries in buildings. They’re resilient. If you see a window that is sagging or drooping, it is not the glass breaking down—it’s the lead.

PART 4 : RELIGION

JUDITH

I was raised an atheist by passionate atheists. There is something about radiant, colored light that casts radiant, colored shadows that is, to this atheist, God-like. So yes, I do think that radiant light is actually spiritual.

BEN

There’s a weird sacrilege to [the cars]. The church could be mad at me for doing this. But I think there’s an argument about these being installed, originally, to bring people closer to God—and now, these churches are torn down and the glass won’t see the light of day again. I’m revitalizing them, and applying them to automotive.

MOSES

There’s just something about a Porsche that’s magnetic.

BEN

A lot of people, when I show these cars, are getting really close to it, scanning it for a long time. It sparks spiritual conversation.

DIANE

There was a real religious revival in the 19th century in the United States. A lot of immigration, and a lot of churches being built. Many of them wanted windows, so a lot of companies were making them. Supply and demand! You can follow the money by looking at the churches where these windows existed. There had to be money in those congregations.

DAVID

Some of the patrons that donated money to build the church would also be found somewhere in the stained glass. In medieval times, especially, their contributions were a reflection of their afterlife. An immortal reminder for the clergy to remember them in their prayers, and for the congregation to see “these were good holy people”—no matter if they were or not.

JUDITH

I am less of an atheist now, for what it’s worth. But that’s maybe because I’ve been doing stained glass for too long. [I’m] hopelessly addicted to it.

Author’s Note: Thank you to Amanda Gordon of the Museum at Eldridge Street for sending me to the East Window. Additional gratitude to the New York Public Library’s Picture Collection, which assisted in the visual research for this piece, and to Seth Caplan for originating this collaboration at large.

Select dialog has been edited for clarity.

Emily R. Pellerin is a writer, marketer and strategist with a focus on creative communities. As a consultant, she works across sectors to translate ideas into content, brand identities, and life-sized projects. Her clients range from creative studios and design firms to non-profit organizations, to individuals and global-scale companies doing fun, clever, ambitious work. As a researcher and reporter she covers the art and design spheres, and issues at the convergence of the built, social, and natural environments.

Seth Caplan is a New York-based commercial photographer, arts educator, and artist. His photography spans interiors and portraiture and has been published in titles such as Architectural Digest, The New York Times, and New York Magazine. His personal work often explores identity, queer community, and home. As an educator, Seth teaches art to groups of all ages in museum galleries. When not with his camera, you can find him making ceramics and swimming in the ocean.

Product specialist at Manhattan Motor Cars, a luxury1b vehicle dealer // 1b: Like, very luxury

Glass artist and classic car aficionado

Photographer

Senior Curator of Glass and Contemporary Craft at Toledo Museum of Art

Pioneering American glass artist and “one of the world's premier stained glass artists,” according to the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, where she was an artist-in-residence

Associate Rector at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Savannah, Georgia

Glass Visions Studio occupies a former motorcycle shop

Referring to Super/Natural (2025), her human-scale, stained-glass dome

Fantastic piece with such a creative structural approach - so perfectly aligned for the topic. Will be thinking for a long time on the contrast inherent in such a delicate but physically immense craft, and the way that this project merges what I've prejudiced as a hard/aggressive passion (car culture) with the beautiful, graceful spirituality I read in stained glass (as a raised-in-church gal myself). Actually LOL'd at Judith's conclusion; just such a good final note!